20 years since Kargil war, these 527 young martyrs still live on

On the 20th anniversary of the Kargil war, ‘Kargil - Untold Stories from the War’ revisits the battle field of Kargil. Author Rachna Bisht Rawat pays tribute to the 527 young soldiers who never came back.

Lest we forget…

With the exception of young readers, who are not yet 20, all of us have lived through the Kargil war. Some of us saw it unfolding on our television screens while others had a closer look.

I was a reporter with the Indian Express, Ahmedabad, newly married to Capt Manoj Rawat of 3 Engineer Regiment when the war broke out. My husband’s unit was among those immediately deployed on the Rajasthan border because of a perceived threat.

Saurabh Kalia's father at the shrine dedicated to his martyred son in his house. Saurabh was only 22 when he was killed in the battlefield. (Photo by author)

Even as I watched with a sinking heart, the entire cantonment emptied of men and machines within a few days. Noisy Messes where ice cubes clinked in crystal glasses were suddenly quiet, the stomp of DMS boots was not heard in parade grounds anymore, parks no longer rang out with the laughter of dads throwing balls to little children with poised bats.

I would stand in my balcony and watch convoys of Army trucks headed for the border carrying soldiers in combat greens, rifles slung across their backs, faces sombre. My handsome husband bid goodbye with a curt handshake since an officer will not be seen hugging his wife in front of his troops. He did smile lovingly at me from the driver’s seat and, with a crisp salute, told me to take care; he would be back soon. He then drove off; his jeep disappearing in a cloud of dust.

The solace of my life is that he did return. So many husbands never did.

The war was eventually restricted to Kargil. My 25-year-old brother, then Capt Sameer Singh Bisht, fought it alongside his unit 5 Para. Those were terrible days indeed. I would scan every newspaper, watch every news channel, stay awake in my bed, shared with Sufi the cat, waiting for dawn to break.

In the morning I would go to work and beg, borrow, steal any war-related assignments I could from my editor Derick D’Sa. Accompanied by a photographer, I would travel to villages where the bodies of martyrs were being brought home. I would cover funerals, join processions, and watch grieving families and little children whose lives would never be the same again.

The book cover (Image: Penguin)

I would think of the men in my life who were at risk too and my heart would sink. Late evenings, returning from office, I would park my bright blue scooter at an STD booth and call up home in Kotdwar, a small town in Garhwal, where my parents lived in a bungalow surrounded by mango trees ever since my paratrooper father Brigadier BS Bisht, SM, VSM, had retired.

It was always mom who picked up the phone. Dad, she said, was glued to the television watching war bulletins, trying to figure out where my brother could be.

He had almost stopped eating and would sit silently in the verandah late nights with the light switched off; his head held high, a smoking cigarette dangling from between his fingers, glass of whiskey by his side, Farida Khanum’s voice wafting out of our sitting room window from the old cassette player inside.

His suffering ended when his son returned from Kargil a decorated officer. He was lucky. There were many whose sons never did.

In the course of writing ‘Kargil’, I met some of these fathers. And mothers. And children with hazy memories of that man called father, a stranger in olive green who had left home one day and never come back.

When I asked Kargil martyr Lance Naik Bachan Singh’s son Lt Hitesh to share some memories of his father, he said he hardly had any. “My twin brother and I were four when he died, but I do remember his funeral,” he told me.

Mrs Kamesh Bala told me that in seven years of marriage she had spent just five months with her husband. He had promised to take her and the twins along in the peace posting he was expecting but that day never came. Bachan died at 29 in the Battle of Tololing.

Saurabh Kalia's mother with the cancelled cheque. (Photo by the author)

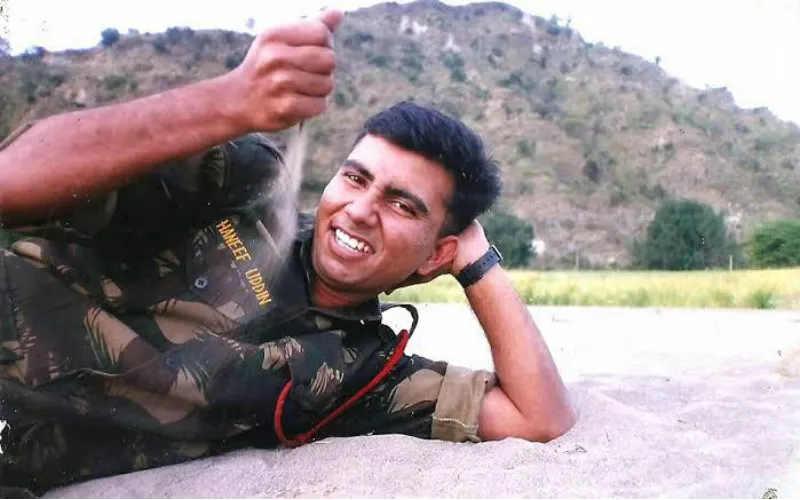

Capt Saurabh Kalia was 22 when he had signed the first cheque of his life soon after being commissioned and had handed it to his mother proudly, telling her, “Don’t worry about money anymore, ab mein kamane laga hun (I have started earning now).”

Mrs Kalia showed me the cancelled cheque with tears in her eyes. It was never cashed. Saurabh was dead before his first salary was credited into his bank.

Mrs Meena Nayyar told me how the pampered Anuj would keep pestering her and his dad for a new car that he wanted them to buy him before he got back. “I would get exasperated each time the phone rang. We didn’t think he would never return,” she said. Anuj was to be married to his school sweetheart in September 1999. In July he was dead.

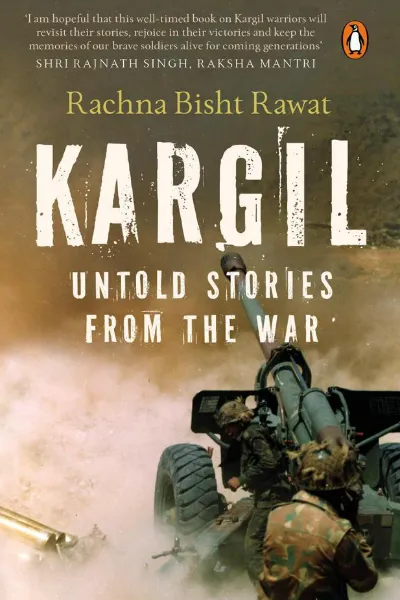

I met Capt Haneef-ud-din’s mother Mrs Hema Aziz. Haneef’s body lay on the frozen snow in Turtuk for 43 days. When the Army Chief Gen Ved Prakash Malik visited Mrs Aziz and told her that they were not able to retrieve his body because the enemy was firing constantly, she assured him that she did not want another soldier to risk his life to get her son’s body. She even refused the petrol pump that was offered to her on Haneef’s martyrdom.

Capt Haneef, who was only 24 when he died on the Kargil battlefield, photographed by his colleagues in happier times. (Photo from the book)

I am sure there are heartbreaking stories like this on the other side of the border as well. I marvel at how men who are fathers, sons, brothers, husbands, lovers, just lace up their boots and go for war, honouring their sole responsibility as soldiers.

War stories might sound romantic but the reality is that war is terrible. It destroys lives, shatters families and leaves behind a legacy of sadness and hate. I sincerely hope that the martyrs of Kargil were the last ones we have had to grieve.

This book is a tribute to their courage and, even more so, that of their families, who have faced their loss with such dignity. We are under their debt; a debt that can never be repaid.

Vijyant Thapar was 22 when he was martyred during the Kargil war. (Photo from the book)

In his last letter to his father, Lt Vijyant Thapar had hoped that the sacrifices of his men would not be forgotten.

This book is a step in that direction. I hope that Kargil – Untold Stories from the War will keep the memories of these brave men alive in public memory. Because that is the least we can do for those who willingly gave up their lives for the country.

Soldiers don’t die on battlefields, they die when an ungrateful nation forgets their sacrifice. May the 527 martyrs of Kargil live in our hearts forever.

‘To live in the hearts we leave behind, is not to die’ – Thomas Campbell

(This is an exclusive excerpt from the book 'Kargil - Untold Stories from the war' published by Penguin which is available for pre-order)

![[Techie Tuesday] Meet ex-Zynga CTO Cadir Lee, who now dons many hats in the startup world and beyond](https://images.yourstory.com/cs/2/730b50702d6c11e9aa979329348d4c3e/Techie-Tuesday-Cadir-Lee-1581942094923.png?mode=crop&crop=faces&ar=1%3A1&format=auto&w=1920&q=75)