Thamimunissa Jabbar and her team from Chennai that’s hitting the right goals

Creating champions in short periods of time isn’t new or unnerving for Jabbar, the powerhouse coach in a burqa, who has led her students to victory in district, divisional and zonal championships, with less than two weeks of training.

Rafia Fathima is 12. She loves getting high-fives and burgers from KFC.

But if there’s one person who can keep her off the greasiest grub, it is her football coach Thamimunissa Jabbar. Jabbar is currently up to her neck training a team of 20 girls—a majority of whom come from orthodox Muslim homes—for the upcoming state football championship that her academy, Talent FC, is hosting in Chennai on April 30. Time is of the essence this year, as most players started training barely two days ago, after a long Ramadan break.

But creating champions in unprecedentedly short periods of time isn’t new or unnerving for Jabbar, the powerhouse coach in a burqa, who has previously led her students to victory in district, divisional and zonal championships, with less than two weeks of training—all with the hijab on.

“It may seem like a simple statement, but it is often what reassures parents that their children are in good hands,” says Jabbar.

Over the years, she has emerged as a matriarch of sorts for numerous young girls from conservative Muslim families who aspire to find a sense of identity in football while staying rooted in their values.

She has brazenly taken on referees in state championships to ensure her girls get to play with their headscarves on, spent months personally engaging with their families, and seen to it that they never skip school, reach home before sundown and excel in their exams. “For most families who are opposing, these are non-negotiables,” says Jabbar. “They are also principles I personally stand by.”

Rafia’s father Mohammad Rafiullah says Jabbar’s accountability and conviction that football can change the life of her students, was the first thing that persuaded him to send his daughter to train under her.

“Many times, there are religious beliefs that restrain Muslim families from sending their daughters to play tournaments in other cities with a woman coach. There are others who worry that their daughters may come back tanned playing in the sun, or get into some sort of danger without male supervision. For me, seeing my daughter happy and getting good at her game was the final push,” he says.

There’s no one who understands the immense value behind such transformation in the hearts of families better than Jabbar. Among the things that make her a feisty champion of young female players’ right to football is her own unrelenting struggle to follow her dream.

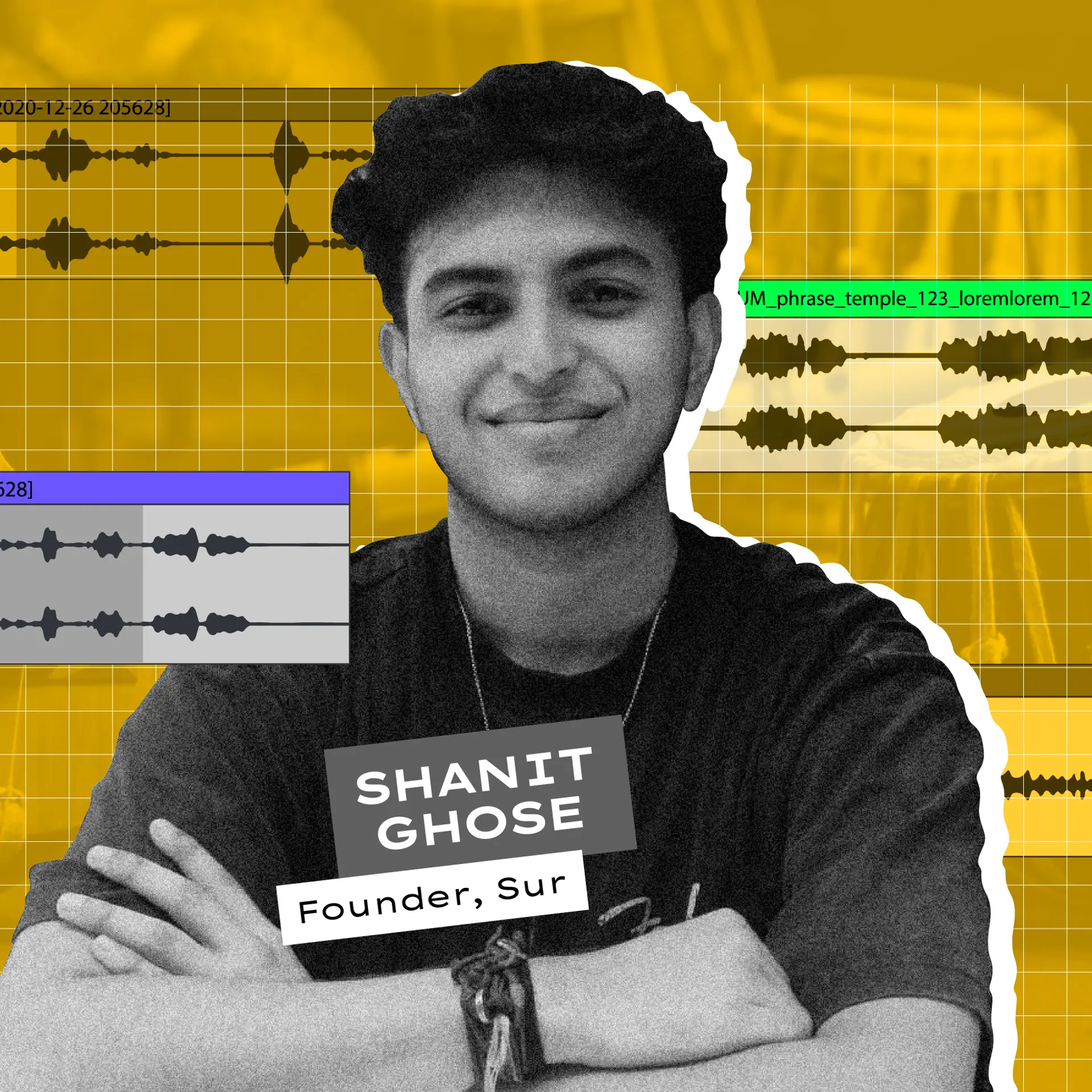

Thamimunissa Jabbar

Her tryst with football began in 1997 when she was a student in Chengalpet. In less than two years of playing, she went on to win a state-level match in Kanchipuram. The victory however wasn’t earned without a painful cold war with her parents that ended only after she won the 1999 Tamil Nadu state tournament in Ooty.

“My father teared up as he read news reports about me and said he was glad I stood my ground,” she says. “But if it wasn’t for my coach who assured my family that I had a promising future in this game, I would have been married the moment I turned 18,” she says.

In her seven years as coach, Jabbar has gone great lengths to retain talented girls in the team. To help those from underprivileged backgrounds, she has packed nutritious meals from home, so that they consistently stick to a robust diet. She has also fully sponsored a bootcamp for her team during school vacations and cooked meals for them every day alongside training. And yet, there are hardly any girls who have stayed with her after they finished school.

“There is little I have been able to do with the older girls, because the moment they turn 18, the only thing their families want for them is marriage,” says Jabbar.

Twenty-one-year-old Shamna Rahman is Jabbar’s only older student who continues to play. She is now a coach herself, and in many ways, is taking Jabbar’s legacy forward in reclaiming football for those who may otherwise have negligible opportunities to find the game.

“I started training under Thamim in 2008. And a lesson she has set in stone for me is to celebrate even the smallest of victories - starting from a school competition,” says Rahman. “The only way to get your family, community or society at large to see beyond their fears and stigma is to demonstrate what you are capable of on the field. When you become a football champion in India where the game is still largely unsung, you stand out for the whole world to see and celebrate you.”

Edited by Akanksha Sarma