The Innovation Code: how to harness the Artist, Engineer, Athlete and Sage in your organisation

Drawing on their work with nearly 200 of the Fortune 500 companies, innovation experts Jeff and Staney DeGraff have developed a framework of four different styles of innovators and how to constructively engage their tensions to create organisational innovation.

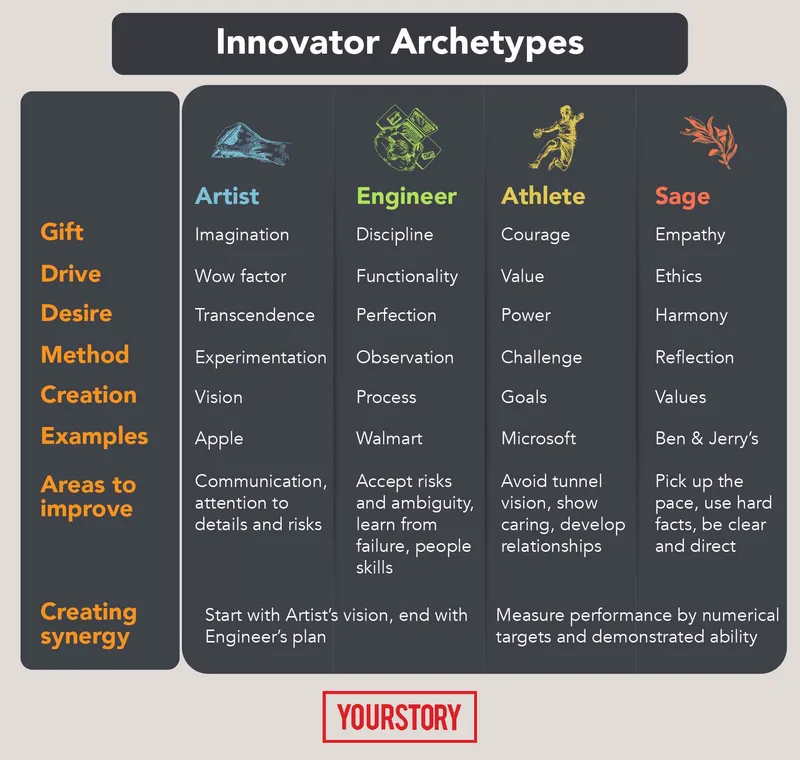

Creative people have different kinds of worldviews, which are their strengths (competencies) as well as weakness (blind spots). Four key archetypes are the Artist (who loves radical innovation), the Engineer (who constantly improves everything), the Athlete (who competes to develop the best innovation), and the Sage (who innovates through collaboration). Archetypes are not to be confused with organisational job titles.

Push and pull need to be encouraged in different doses and phases between the four archetypes, so that positive conflict leads to surprising breakthroughs. The Innovation Code: The Creative Power of Constructive Conflict explains how organisations need to understand, map and nurture such cultural diversity to design engagement processes and competency frameworks for synergy.

Jeff DeGraff is a professor at University of Michigan’s business school. His other books include Creativity at Work; Leading Innovation; Innovation You: Four Steps to Becoming New and Improved; and The Enlivened Self: The Art of Growing. Co-author Staney DeGraff directs the Innovatrium, an innovation institute.

“When it comes to any innovation initiative, disharmony is crucial,” the authors begin. “Innovation is not about alignment. It is about constructive conflict – positive tension,” they say. People of each archetype need to understand these differences and complementarities, and develop a shared vision of how to work together. This method is called the Innovation Code (I have briefly summarised the individual and group-level issues in Table 1).

Startups and innovative companies are not necessarily harmonious organisations – their success (or eventual failure) lies in how they sustainably manage creative tension between these different personality types of innovators. Internal conflict and challenge can actually make innovations more resilient.

Innovation is hard and even hurtful work in an organisation, and managing (not eliminating) constructive conflict is one of the difficult aspects of organisational creativity. (See also my reviews of the related books Innovation is a State of Mind, Originals, The Innovation Formula, and The Innovator’s DNA.)

The Artist

The Artist archetype is a gamechanger, radical innovator, out-of-the-box thinker, high-risk high-reward creator, a wild experimenter who rejects convention. Artists are imaginative dreamers and revolutionaries constantly searching for something new, and envisioning new products or services.

Examples include Walt Disney, Steve Jobs, Larry Page, Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, Gianni Versace, Coco Chanel and Duke Ellington; companies include Pixar.

The Artist is good in the earliest stages of development of a company, and then during later stages of reinvention. For example, Apple started off as an ‘Artist’ type of company in the desktop category, then got overshadowed by other players, and only later redefined itself.

Artists are future-oriented, conceptual and optimistic, and willing to accept failure along the way. However, they can also be rebellious and undisciplined, and take too many risks. The organisation needs to work with them by adding more structure and priorities to their projects, and helping match their vision with the needs of others (‘create your own Broadway rather than just be on Broadway’).

The Engineer

The Engineer archetype strives for incremental innovation and seeks efficiency, quality, systems and processes. They are highly disciplined and see the value of bureaucracy. They prefer growth that is low-risk and slow-moving.

The focus of an Engineer is something not necessarily newer but better, cheaper and faster. After all, not all innovations have to be sexy, cool, chic or glitzy. Innovation also happens behind the scenes and is embedded deep in processes. Engineers are ‘under-rated back-office superstars,’ the authors explain.

Engineers develop streamlined reliable procedures that minimise failure and can be replicated and scaled. The Engineers are thoughtful and sensitive – as well as pragmatic, methodical, objective and persistent. But they can also be authoritarian control freaks who are not that open to new ideas.

Examples of Engineers include Sam Walton (Walmart), Michael Bloomberg, Warren Buffet, Dell, McDonald’s, Boeing, Toyota, Marie Curie, Carl Sagan and Xi Jinping (President of China).

The Athlete

“The Athlete represents a Darwinist approach that focusses on competition where the strong prevail at the expense of the weak. The Athlete understands that time is essential for innovation. Innovation can go sour, like milk,” the authors explain. Athletes are results-driven workhorses - they seek power and produce profit and speed.

They are aggressive, action-oriented and want to win at all costs. They have courage and are willing to sacrifice; after all, innovation is not just about creativity, but also courage to create and accept change. They are good in portfolio-ways of thinking, deal-making and public image. Athletes create an atmosphere of winners and losers.

Such companies are focussed on competition and want to be not just successful but right at the top. “The organisations that don’t even realise they’re in a competition are always the first losers,” the authors explain.

But Athletes can be ruthless and short-sighted, and don’t see the long game; they want instant victory and not as much of community and durable culture. Innovation is not just one race, but an infinite game, and Athletes must be open to new trends and keep reinventing the playbook.

Examples include Tim Cook (Apple), Indra Nooyi (PepsiCo), Jamie Dimon (JP Morgan Chase), Microsoft, GE, Goldman Sachs and Angela Merkel (Chancellor of Germany).

The Sage

The Sage seeks connection, harmony, togetherness and community. They are mentors, facilitators, counsellors and team-builders who work on shared values and grow industry knowledge. They are empathetic and understanding listeners. They value lifelong learning and re-learning from like-minded as well as totally different people.

Sages like to let others also speak, and thrive on building a culture. “What Sages show us is that culture creates the economics of innovation,” the authors explain. Sages seek collaborative innovation via a broad range of inputs from within and outside their networks.

But their greatest gift – patience – can also be their downfall in today’s breakneck race of innovation. Sages are slow to act and are unassertive; they can be unclear in direction and let emotion overrule logic.

Examples include Florence Nightingale, Martin Luther King Jr., Oprah Winfrey, Jostein Solheim (Ben & Jerry’s), and NGOs like Doctors without Borders and Habitat for Humanity.

The Innovation Code: working with the four archetypes

I have briefly summarised the key traits of each archetype in Table 1, and how they can be managed in innovation activities. The second part of the book discusses how to creatively resolve the typical conflicts between Engineer and Artist, as well as Athlete and Sage (but not other combinations of these types or even within these types, eg. between two Athletes).

Each archetype has implications for the magnitude and speed of innovation, as well as timing in the organisation’s growth. Artists and Athletes are good at launch stages, and Sages and Engineers contribute to long-term sustainability. Typical timelines include formation (Artist), playbook (Athlete), community (Sage) and hierarchy (Engineer) - then the entire cycle needs to be repeated for reinvention.

Combining innovation from the Artist and Engineer gives results that are revolutionary and low-risk, complementing extreme creativity with process reliability. The Athlete-Sage combination gives innovation that is both a good investment and good for the world, with a blend of tangible outcome and long-term values.

“While Artists shake up the rules of Engineers, Engineers minimise the chaos of Artists,” the authors explain. “The killer instinct of an Athlete and the social intelligence of a Sage is a dynamite combination,” they add.

“Constructive conflict is conflict with empathy,” the authors say. Conflict can cause discomfort – but innovative companies should get used to it and become courageous. “Conflict must become normative,” the authors advise. Worldviews will be regularly challenged; growth requires pain.

Developing a shared vision, engaging in creative conflict, and constructing hybrid solutions are key steps for success with these diverse archetypes. Scenario planning and rapid prototyping are useful ways to engage the archetypes.

Facilitators, mediators and consultants can bring these various types together by using metaphors and analogies to describe the shared vision and design collaboration projects, eg. building a garden, preparing for a marathon. The goal should be variety without discord, and cooperation without necessary consensus. Having a board of advisors also helps.

For example, John Lennon (Artist) and Paul McCartney (Engineer) had very different approaches to music – but Brian Epstein’s role as a mediator helped the Beatles produce some of the best songs of all time. Producer George Marin regularly reminded them of time constraints in the recording process.

In the long run, companies should establish an everyday culture of curiosity, learning, and collaboration. “A culture of everyday learning is the new normal,” the authors explain. The biggest breakthroughs are powered by networks, motivation, sharing and collective vision.

Your own internal innovation code

The book ends by describing how we each have elements of these four archetypes within us, and their intensity can also change over time. “Managing your inner team is a constant rebalancing of all these various identities,” the authors explain.

Self-awareness and reflection are key skills to have in this regard. According to developmental psychologist Howard Gardner, we need to be aware of and nurture our eight types of intelligence: visual-spatial, bodily-kinesthetic, musical, interpersonal, intrapersonal, linguistic and logical-mathematical. As our skills, dreams and definitions of happiness evolve over time, we will each need to switch on, switch off and mix these inner archetypes to find our calling in life.

The book also opens the door to other interesting research areas. How should founders balance their own archetypes with others in the core team? How should manager succession planning be handled to introduce new archetypes or preserve existing ones? Are there variations of or additions to these four archetypes in other countries of the world - such as, say, China and India?

In sum, the slender book (140 pages) makes for a quick and practical read; online tools are available at the book’s website. More case studies along with a list of references and suggested reading would have been a welcome addition to the material.