10 languages across 40 countries: this storyteller’s initiative spins a tale of inclusion for the disabled

Reviving the lost art of storytelling, Ajay Dasgupta’s The Kahani Project is making stories accessible to children across all nationalities and disabilities.

For The Kahani Project, it’s been five years of spreading smiles through stories. Started on the eve of Children’s Day in 2012, the team at The Kahani Project has crowdsourced over 600 stories on their online repository, which has been accessed over one lakh times.

Milestones in the making

However, for 39-year-old Ajay Dasgupta, the core philosophy behind launching The Kahani Project was never about having an online library of stories.

Our primary aim was to make stories accessible to those children who do not have access, be it those belonging to the differently-abled community or marginalised groups. The website with access to all our stories just became a way of spreading what we do, he says.

Ranging from folklores to fables, The Kahani Project’s open-sourced, online library has access to stories recorded in languages like English, Hindi, Bengali, Gujarati, Marathi, Kannada, Tamil, Telugu, Urdu and Sindhi.

In fact, one of the top countries on our online traffic list is Pakistan. This goes to show that despite the hostilities that exist between both countries we still share the same love for stories, Ajay quips, adding that a huge chunk of listeners are also from the US and France.

Accessibility is the key

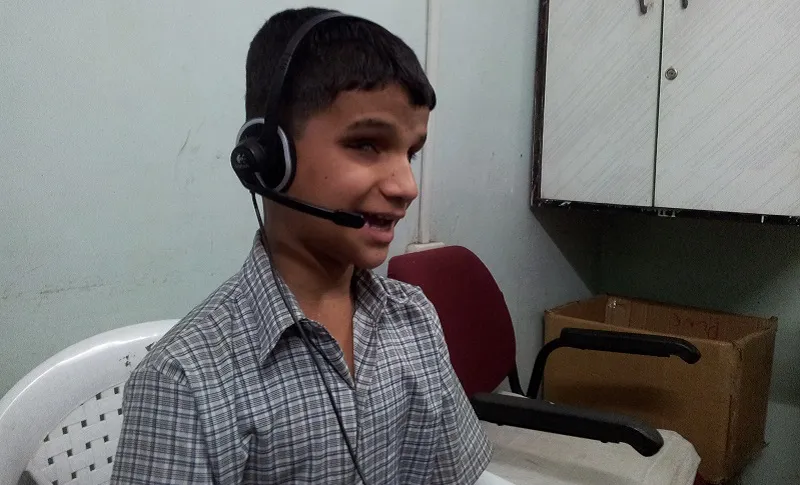

Ajay first took to storytelling in the slums and special schools across Pune. Ajay and his team have also closely worked with the Blind Boys School in Pune. Calling the experience as most impactful, Ajay says,

It’s overwhelming to see how children with visual impairments and cognitive disabilities react after listening to stories. Often, they just don’t want you to leave, and demand we repeat their favourite stories.

Though they still continue to hold storytelling sessions and storythons, The Kahani Project’s ‘free for all to download’ audio stories on their website have opened up new avenues for children across all age groups, nationalities and disabilities to enjoy the joyous experience of listening to age-old stories.

Breaking down the nuances behind accessibility, Ajay explains,

An average 10-year-old child in India attending a public school has access to over 10,000-15,000 books across school and city libraries. If you come to the fringe groups, the number drops to just over 1,000 books. And among the disabled communities, the number reduces to a negligible 10-15 books that a specially-abled 10-year-old can access.

Terming braille as a difficult format to maintain and replicate, Ajay says “We discovered the audio format to be the most easily accessible format to listen to and share. If you have access to an MP3 player, you can download new set of stories from our repository every time.”

Ensuring our folktales and stories live on

Modern technology, access to gadgets, comics, video games and the deteriorating culture of joint families can be contributors to a long-lost culture of storytelling in India. In this context, the Kahani Project hopes they can revive at least some of most legendary fables, folklores and mythological stories that current generation children are missing out on hearing.

“It’s unfortunate that a large number of children belonging to the fringe groups in slums, construction sites, orphanages do not have access to the stories that represent India’s rich cultural heritage. We do not want an entire generation of kids growing up without knowing these stories,” says Ajay.

While Vikram Seth’s ‘Louse and the Mosquito’ remains the most heard and downloaded story on The Kahani Project’s website, collection of stories in Gujarati and those of Munshi Premchand in Hindi rule the chart of top albums.

Once a relevant story is identified, The Kahani Project ensures that enough research goes into it and appropriate filters are applied before recording.

We make sure we do not choose stories that propagate stereotypes, encourage violence or profanity, says Ajay, who takes keen interest in disseminating region specific folk stories that are often inspirational or light-hearted.

Challenges and way ahead

Calling themselves a ‘voluntary group run by the interest of enthusiastic individuals’, the team is not very keen on scaling up in a big way.

“People often confuse us for a startup or a non-profit. But we have only grown by the support and acceptance of people. It just goes on to show why almost 90 percent of stories are recorded by volunteers and public,” says Ajay.

In fact, the biggest hurdle so far has been about ensuring something of this scale runs sustainably without being an organisation, he adds.

The Kahani Project is hopeful about uploading more stories to reach the 800-mark by end of the year. “The future plan is to ensure we record and publish at least 50 stories a month. We are also working towards launching a podcast channel with fortnightly programmes for children,” says Ajay.

Ajay and his team are also optimistic about raising funds to procure more MP3 players that would help them hold storytelling sessions in various special schools across the country.

“With our limited, self-sponsored budget, we have been able to reach only 250-300 differently-abled children. We plan to expand our outreach in the coming days. However, we still prefer the crowdfunding way rather than take the CSR approach,” specifies Ajay.

So, what keeps the ‘kahani’ going?

It’s the joy of storytelling in itself. The smiles on children’s faces is what matters the most. The hits and downloads on our website, though encouraging, cannot match up to the delight of children who love listening to stories, concludes Ajay.