The Bose family and Netaji’s escape

Nandita, daughter-in-law of Sarat Chandra Bose, recounts Netaji’s grand escape from house arrest in 1941.

Subrata Bose, Sarat Chandra Bose’s son, as I had known him, was quiet and courteous. He could debone a fish perfectly with a fork and a spoon, and his aura was one of erudition. A few years after his demise, I sit with his wife, Nandita Bose, on the eve of India’s celebration of 70 years of freedom while she shares family anecdotes. Her stories are punctuated with laughs and instructions to ‘eat more’. Independence Day has been quite a grand affair for the family, recounts 77-year-old Nandita.

She remembers the flags being hoisted and the processions passing by in 1947 when she was a mere girl of seven. Later, at 22, when she married into Bengal’s well-known Bose family, Independence Day meant invitations to attend a variety of events.

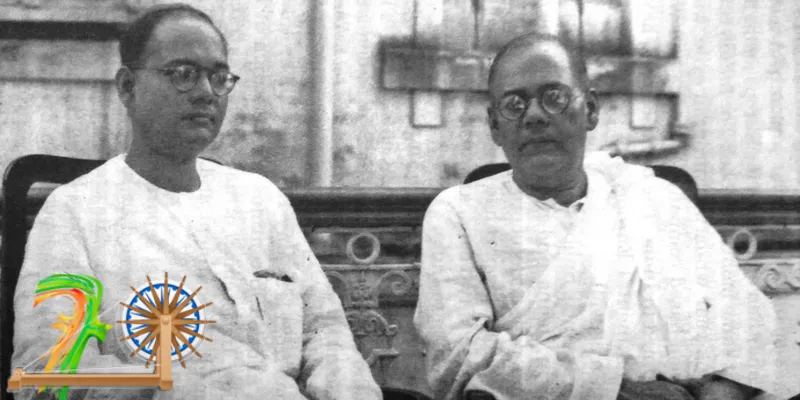

The two brothers

Sarat had left the family home at Elgin Road, Kolkata and set up his own abode nearby at Woodburn Street. His son, Sisir, was Subhas Chandra Bose’s compatriot in the grand escape that has gone down in history as the last time this country saw one of its greatest revolutionaries.

In 1941, 44-year-old Subhas was under house arrest. Policemen kept guard outside his home. Sarat had suggested that the escape should seem like an ordinary journey. “He did not want anyone to suspect that there was something amiss. Let it be in the guise of something that happens every day, he had said. Such foresight!” exclaims Nandita.

Every day for two-and-a-half months, late at night, Sisir would drive to Subhas’s house. When policemen stopped him, he would tell them, “My uncle wants to listen to the radio broadcast about the Second World War. He is too ill to tune the transistor himself. So, he depends on me to do it for him.”The guards let him pass. “My father-in-law taught him this response,” Nandita points out.

Some other cousins in the home had to be taken into confidence because there were too many people for the matter to be safely kept under wraps. One of them, for instance, was to cough as a signal that the car with Subhas and Sisir in it had left the premises of the ancestral home.

For days, Subhas did not shave nor meet any visitor. Every chance of encounter was avoided so that none could claim to have seen him, nor would stand the opportunity to suspect that he was bound for an escape. His food was pushed into his room through the doorway.

Sarat wanted to be sure that his brother had passed safely. He stood on the terrace of his house, and when the car went by, the travellers flashed a torch.

Sarat Bose wanted an undivided India, recounts Nandita.

He had resigned from the interim government over a tiff with Jawaharlal Nehru and Vallabhbhai Patel. Subhas too, with his patriotic zeal, fought unto death for an unfettered, uncorrupted, undivided nation.

Read More:

How the Indian National Army was born in exile, 3,000 km from home

‘He went mad after he woke up’- experiences of black terror in Andaman’s ‘Kala Pani’ jail

Story of Rifleman Jaswant Singh Rawat, whose valour impressed even the Chinese commanders

The escape

The car stopped at the Rishra home of relatives Ashok Nath Bose and Mira Bose, on the way to Gomo railway station. To her surprise, a servant informed Mira that there were two unexpected guests for dinner – Sisir had brought ‘a handsome Muslim man’ with him. While the disguised Subhas waited in the drawing room, Sisir took Ashok into confidence. Dinner that night was a quiet affair. Mira later recalls that the servant reported, “The Muslim gentleman said that the cabbage was tasty.”

“To talk about cabbage in the midst of all this!” Nandita laughs as she tells me a story that she has, perhaps, recounted to many rapt listeners.

On the way to Gomo station, Subhas sat in the front seat while Sisir drove. Ashok and Mira were seated at the back. Subhas decided that Mira, who was then a young bride of 18, should know what was going on. She, needless to say, was dumbfounded. But, Subhas calmly kept turning to her and reminding her to never breathe a word of this to anyone.

At the station, he laid an affectionate head on everyone’s head and asked them to wait in the car. No need to see me off, he had said. Sisir insisted on walking on the platform, pretending to be another passenger, to see his uncle board his carriage. Policeman rubbed tobacco in their palms and kept guard as Bengal’s most sought-after revolutionary escaped them calmly, quietly in plain sight.

I remember reading a biographical account of Subhas’s escape, in my school textbook. It compared him to the light of the train that had sped off into the darkness of night. That light was all I could think of as Nandita finished her story.

One day in 1945, Emile Schenkl, Subhas’s wife was doing the dishes. The radio announced that India’s Subhas Chandra Bose had met with a plane crash. And, his life was deemed to have ended suddenly.

The national goal is to me at least as clear as daylight. It is an independent republic free from British control... An independent India has been the dream of my life and I believe it shall be a fact in Indian history- Subhas Chandra Bose, Behrampore Jail, December 1924.

Enter the SocialStory Photography contest and show us how people are changing the world! Win prize money worth Rs 1 lakh and more. Click here for details!