Are Swiggy's ambitious plans turning its partner restaurants into rivals?

Swiggy, which survived the foodtech bloodbath of 2016, has been called out for ‘overeating’ in a recent controversial anon post by disgruntled ex-employees. However, the important question here is much larger: as Indian startups begin to scale, how much fair is fair?

Controversy seems to be a part of the startup ecosystem. And this time it isn’t the usual e-commerce suspects and contenders, it is, surprise, surprise—Swiggy, the Bengaluru-based food delivery startup that has been the darling of investors and consumers alike.

Last Thursday morning the startup world got a rude shock. A Tumblr blog post titled, “Swiggy, a house of cards,” co-authored by four current and ex-employees in the Sales team at Swiggy’s, alleged that the Naspers-backed food delivery startup has been following shockingly unethical practices.

The accusations ranged from cheating restaurant partners, cheating investors, to a bad work culture and a management that is tough to deal with. Sriharsha Majety, Co-founder and CEO, Swiggy, promptly rubbished the accusations in a media statement and said:

The article carries inaccurate facts regarding business and order numbers. It not only references employee departures from a year-and-a-half back, but also presents details on our partners out of context and with mischievous intent.

Later that evening Harsha also provided a point-to-point rebuttal on the different issues that were raised in the anonymous blogpost, in his own blogpost.

Deepinder Goyal, Founder and CEO, Zomato (Swiggy’s competitor), came out in support, tweeting about the need for transparency. Others dismissed it as a rant of disgruntled employees. Swiggy said it was the work of outsiders.

At the heart of it, the controversy did serve to highlight two points. One is the new set of challenges that players in the rapidly evolving foodtech space will need to deal with very soon. The second is how the sector can grow while ensuring a win-win for both restaurants and delivery companies.

Changing the way people eat

There’s no doubt that food tech startups have been transforming the way people in metros eat. You no longer have to survive on instant noodles or scrounge for leftovers. Simply whip out your phone and order anything you like from platforms like Swiggy, Zomato, or directly from FreshMenu, Faasos, InnerChef and others.

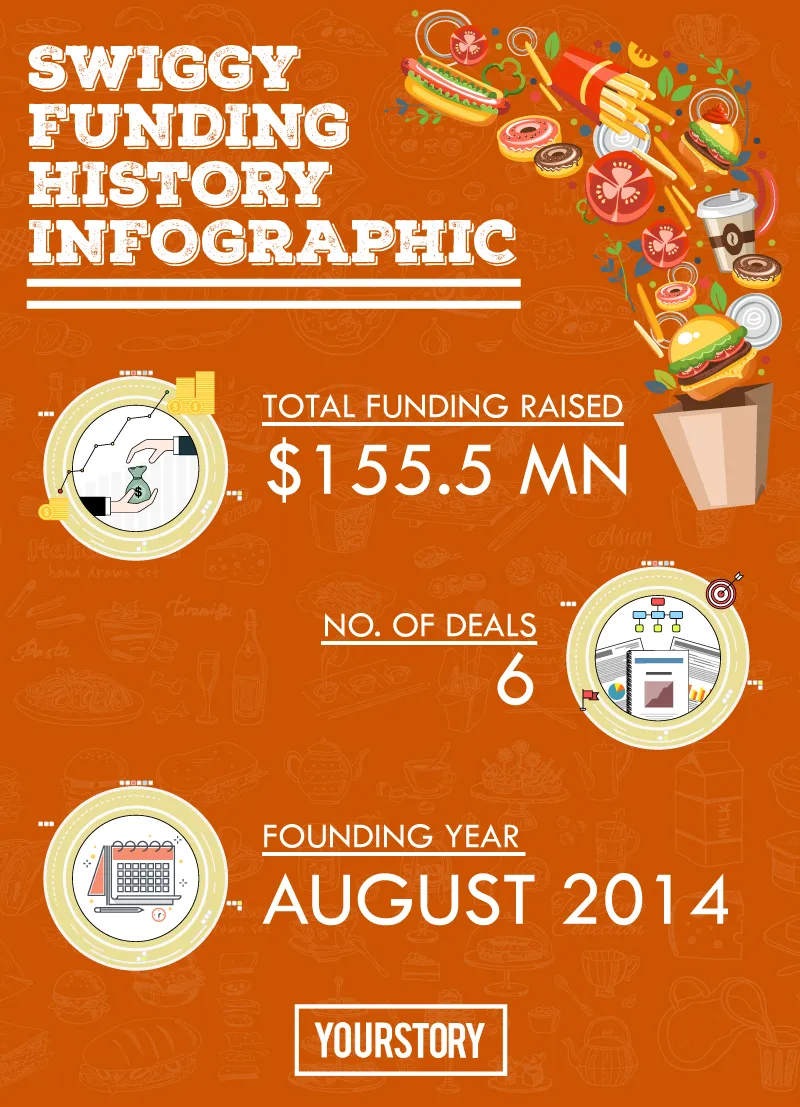

When Swiggy first started operations in August 2014, its main proposition was to ensure that they deliver food from not only high-class restaurants but also pocket-friendly joints and everything in between.

The next eight months saw Swiggy raise $2 million in funding from Accel and SAIF Partners. In May this year, Swiggy roped in media conglomerate Naspers and raised $80 million in a Series E round, taking total funding raised to over $155 million from six investors.

During this journey, it saw rival TinyOwl grow, falter and retreat to just Mumbai. Rocket Internet-backed FoodPanda, which had gobbled up smaller players, was acquired by Delivery Hero earlier this year. Swiggy survived the foodtech bloodbath of 2016 to emerge seemingly stronger than ever, and well positioned to face new competition: uberEATS made a grand entry with a launch in Mumbai and later in Delhi. Zomato, the undisputed king of the restaurant review space, entered the food delivery market. For Swiggy, that was just one more competitor—it had the first mover advantage and was miles ahead.

An entrée of ever-increasing margins?

This is where the Tumblr post claims Swiggy got greedy, and that it was arm-twisting restaurant owners into increasing its margins when contracts were re-negotiated. (As per Swiggy’s statement, contracts are re-negotiated every six months.)

The restaurant business involves high investments in space and equipment. Operating expenses are also high, with raw materials’ contracts and staff—for every minute these aren’t utilised, they lose value and hit margins. The only way to make money is to ensure a growing number of orders—that’s what Swiggy brings in.

Today, apart from the restaurant chains and bigger players, Swiggy also works with small restaurant owners, who form a big part of the unorganised restaurant business. For many small restaurants, Swiggy is the primary route through which orders flow in.

Restaurant owners claim that they started out by paying six to seven percent margins. Margins have increased to 10 percent, then to 15 and now are 20 percent. According to the anonymous Tumblr post, Swiggy intends to hike it to 25 percent and more. So, if there is an order of Rs 1,000, Swiggy gets approximately Rs 250.

Said one restaurant owner on condition of anonymity,

“As order volumes through Swiggy keep increasing, restaurants factor in that demand and work on adding to their daily (raw material) procurements. But then after a point, you start paying the customer for eating food, with each increase in (the) margin (i.e., the amount paid to Swiggy).”

Riyaz Amlani, President Restaurant Association India, and CEO of Impressario Group, says,

“The increase in margins have happened in quick succession, with the move from 15 to 20 percent happening in a span of 12 months. Restaurants have been unable to cope with the pace of this change. These higher margins are for the small restaurants. The bigger ones can afford to hire independent delivery partners, but for smaller restaurants, this becomes difficult.”

However, according to Swiggy, they have been open about the shifts in their contract. Swiggy’s statement refuted that it took 30 percent of an order from restaurants. It further explained:

“Revenue per order (the 30 percent that is being talked about) is a blend of three parts, the commission we get from the restaurants, delivery fee charged from the consumers, and discretionary advertising revenues.”

The statement added,

“We have and will never burden our restaurant partners to levels where they find working with Swiggy untenable.”

There is no denying the value that Swiggy has brought to these restaurants. To several of them, Swiggy gives close to 5000 orders in a month. Some restaurant owners have found other ways to make the relationship work.

“In the past three months, we have had over one lakh orders across all our restaurants in the city, but the problem is that with the dynamic margins, we have had to increase the price of our products on Swiggy. It is the only way we can sustain,” the owner a chain of 11 small restaurants in Mumbai told YourStory.

So what’s distasteful about the main course of action?

Margins aside, Swiggy has bigger plans. In January this year, it launched a pilot to mark its entry into the online restaurant (aka ‘cloud kitchen’) space with The Bowl Company—in direct competition to players like FreshMenu, whose meals are also available on Swiggy. The Tumblr post alleged that Swiggy was giving pride of place on the site to The Bowl Company in the zone where it operates so that it’s the first thing that hungry customers see.

Their concern is now centred around The Bowl Company and the effect it will have on their businesses. A dosa joint owner in Bengaluru told YourStory that Swiggy does not share consumer demography data and details with the restaurants. He adds,

“By using this demography and data Swiggy has created The Bowl Company. If we were to independently run any kind of campaign and marketing initiative with the client, it isn’t going to happen. This is because Swiggy knows the demography and we are unaware of it. To top this, they are white labelling The Bowl Company so that the end consumer sees Swiggy’s restaurant first.”

Also read: Is this the end of the honeymoon period for foodtech startups?

From aggregator to competitor

The problem with this, explains Mohit Gulati, Founder and Investor at Altius Ventures, is that restaurants do not have the same kind of stickiness brands have. When a customer is hungry, they will order what is seen right on top and not bother too much. The selection and decision-making happens only before hunger strikes not when it strikes.

Another restaurant owner however believes that it is all about business and markets at the end of the day. “How will Swiggy make money otherwise? It is a business and needs to look out for itself and its investor’s interests,” says Amit Roy, Founder ThinkTanc.

Ultimately, it’s all about negotiation. Many restaurant owners also allege that when uberEATS began operations they were looking at 30 percent margins, and when restaurants refused those kinds of margins, the rate dropped to 22 percent.

“Why can’t they be transparent? They can share demography and details and charge a flat fee. Let it be a win-win situation for both the restaurant owners and Swiggy. By using consumer demography data to start The Bowl Company and directly compete with restaurant owners is unfair,” asserts Riyaz Amlani.

Swiggy’s rebuttal to these allegations has been that it is working with restaurant partners to help them increase their service footprint by setting them up in its own cloud kitchen. The first such kitchen is in the works and Swiggy said that up to three restaurant partners would be co-located there.

Why now?

This is how the market dynamics function, especially, with players that are disrupting a norm. It goes through the swing of the pendulum from one side to the next before a balance is found. Much like cab aggregators looking for a balance by trying to cut down driver incentives.

“It might not be fair, but it is business. And both sides need to find a way to work together,” says another food entrepreneur.

Culture is what culture eats

The anonymous blog post also brought to light the problem of disgruntled employees taking their grievances online, especially as companies grow.

Sanjay Anandaram, investor and startup mentor, explains that it all comes down to work culture. Every business works towards finding the middle path. There will be problems but how you handle them internally is important.

“We have first-time entrepreneurs who are also first-time CEOs in first-time market categories, being invested in by first-time VCs, attending board meetings and managing companies for the first time. If you add up all these initial experiences, you see that the problem is complex. And now as startups are scaling and growing, they are not used to handling these kind of issues and pressures.”

He adds that it is important to have enough mentors in place to help startups manage such cases and situations.

Mohit Gulati sums it up thus,

“It is unfair at this point to bring out any sort of judgement whether Swiggy is right or wrong. And there are disgruntled employees in every organisation and especially in startups, as they start growing and scaling.”