The unsung Indians who were Nelson Mandela’s heroes

These were the people Mandela studied with; they were his mentors when he joined the African National Congress (ANC); they were the people he had sleepless nightlong debates with, and even danced with; and they were the people who gently moulded the political beliefs of a man who went on to make history.

“Perhaps it requires such depth of oppression to create such heights of character.” Nelson Mandela wrote these words towards the end of his autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom. He wasn’t, however, referring to himself. Like any freedom fighter, Mandela, South Africa’s first black President, was highly influenced by those who fought before him, with him, and in lands far away from him.

In his long struggle for equality, Mandela was highly influenced by Gandhi’s principles of civil disobedience. Although he didn’t entirely agree with Gandhi’s passive approach, he respected what the dhoti-clad, bespectacled man stood for, and applied in any away that he could Gandhian principles to the South African freedom struggle. In fact, hanging on the walls of his home was a picture of Gandhi among Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin; and of these leaders he educated his sons.

Gandhi, however, was not the only Indian that shaped this charismatic leader. Considering that Mandela never met Gandhi, he could be moved by him only so much as history allowed. Following Gandhi’s presence in South Africa in 1893, there was a politically active Indian community in the country – a community that a young Mandela’s political consciousness grew into.

Shaping a young mind

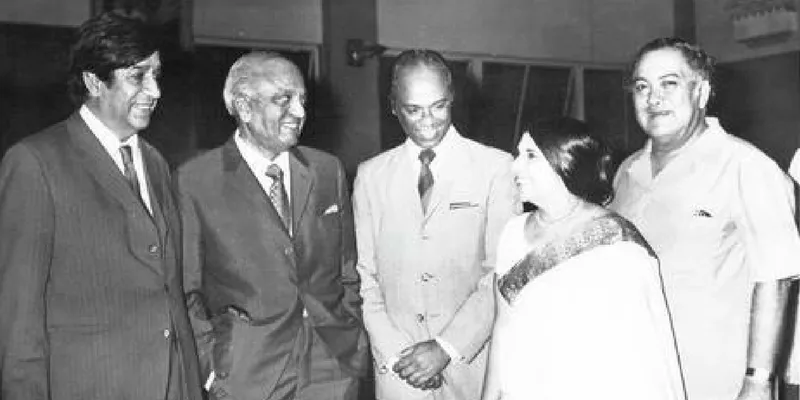

Mandela studied law at University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, which now has a centre named after him. While there, he befriended many Indians: Ismail Meer, J. N. Singh, Ahmed Bhoola, and Ramlal Bhoolia were all part of a “tight-knit group” who regularly met at Meer’s apartment, which had become the unofficial headquarters for the indefatigable politicians and activists in the making.

“There we studied, talked, and even danced until the early hours in the morning…,” recalls Mandela who even bunked there many a night.

This was during the time when Africans weren’t allowed to board trams meant for public transportation while Indians faced no such restrictions. Once, turning a deaf ear to rules, Mandela boarded the tram along with Meer and Singh. When the conductor protested, calling Mandela a ‘kaffir’, the Indian duo “exploded at the conductor” and told him off for using that derogatory name. They were all subsequently arrested and charged for the ‘crime’.

Recalling his time in the university, Mandela elucidates the impact it had on him,

Wits opened a new world to me, a world of ideas and political beliefs and debates, a world where people were passionate about politics. I was among white and Indian intellectuals of my own generation, young men who would form the vanguard of the most important political movements of the next few years. I discovered for the first time people of my own age firmly aligned with the liberation struggle, who were prepared, despite their relative privilege, to sacrifice themselves for the cause of the oppressed.

Indian revolutions moulding a South African leader

In 1946, 28-year-old Mandela witnessed an Indian revolution, which “recast my whole approach to political work”. The Smuts Government enacted a law – the Ghetto Act – that curtailed the free movement of Indians, restricting where they could reside, trade, and their right to buy properties. The Indian community was outraged and considered this a grave insult. The protest, as Mandela recalls, was impressive in its approach and strength:

The Indian community conducted a mass campaign that impressed us with its organisation and dedication. Housewives, priests, doctors, lawyers, traders, students, and workers took their place in the front lines of the protest. For two years, people suspended their lives to take up the battle. Mass rallies were held; land reserved for whites was occupied and picketed. No less than two thousand volunteers went to jail…

Although the rebellion was crippled by authorities, Mandela witnessed “an extraordinary protest against color oppression in a way that Africans and the ANC had not. The Indian campaign became a model for the type of protest that we in the Youth League were calling for,” he recalls.

Mandela was also moved by the sacrifices made by his friends; Meer and Singh suspended their studies, bid goodbye to their families and went to jail. Another friend, Ahmed Kathrada, who was only in high school, did the same. “If I had once questioned the willingness of the Indian community to protest against oppression, I no longer could,” he says.

Grappling with communism

This rebellion also introduced him to Yusuf Dadoo, president of the Transvaal Indian Congress and GM Naicker, president of the Natal Indian Congress, both of whom, along with AB Xuma, signed the Doctor’s Pact in 1947. This was a significant move towards the unity of African and Indian movement and the group left a lasting impact on Mandela.

Dr Dadoo was a well-known Marxist in the circle, whose fight for human rights had made him a hero in the eyes of everyone. Mandela had, until then, strongly opposed the concepts of communism, but amidst the many political arguments with his communist comrades, he felt it imperative that he remedy his ignorance of Marxism. And so, he acquired the complete works of Marx and Engels, Lenin, Stalin, Mao Tse-tung, and others, and probed their philosophies.

Although his studies didn’t successfully convert his nationalistic ideologies, Mandela learnt to amend his harsh views of communists and accepted Marxists into ANC’s ranks. “I did not need to become a Communist in order to work with them. I found that African nationalists and African Communists generally had far more uniting them than dividing them,” he concludes.

Mandela’s respect for Indians, however, did not translate into utter trust. He remained wary of joining hands with Indians and communists and called for African-only campaigns wherever possible. “I was prepared to accept Indians and Coloureds provided they accepted our policies; but their interests were not identical with ours, and I was skeptical of whether or not they could truly embrace our cause,” he says.

Related read: 5 leadership lessons from the life of Nelson Mandela

The Mahatma’s influence, strategically planted

When it came to imbibing philosophies of his Indian counterparts, Mandela was selective; and this strategy didn’t exclude Gandhi. “I called for non-violent protest for as long as it was effective,” he says. Unlike Gandhi, he didn’t consider non-violence as a self-standing principle; he saw fit to use it only when the situation demanded, when it was a practical necessity, and not because it was ethically right. “If peaceful protest is met with violence, its efficacy is at an end,” he would say, although later on, he became more inclusive of non-violence.

His view on hunger strikes too didn’t align with Gandhi’s. He believed that it was too passive a protest. “I have always favored a more active, militant style of protest such as work strikes, go-slow strikes, or refusing to clean up; actions that punished the authorities, not ourselves,” he insisted.

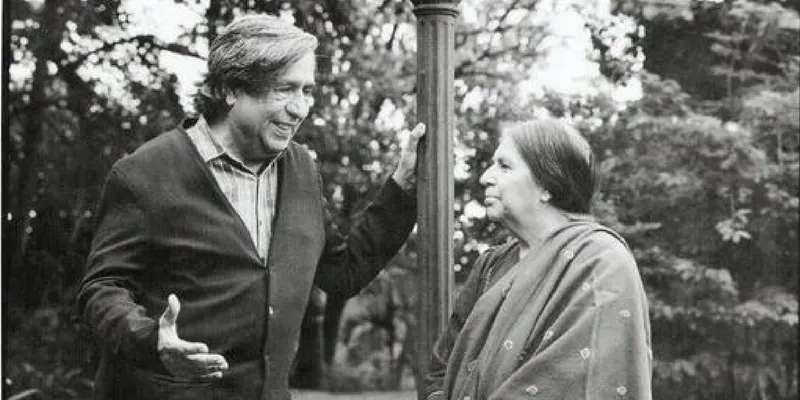

In fighting for the rights of his people, Mandela served 27 years in prison. After he was released in 1990, he made many visits to India for he considered the country and its people close to home.

As the beloved leader would have turned 99 today, it becomes imperative for us to reflect on the values he stood for, and possibly find a way to inculcate them in the turbulent times of today.