How much hustle is too much, and other lessons from the Travis Kalanick saga

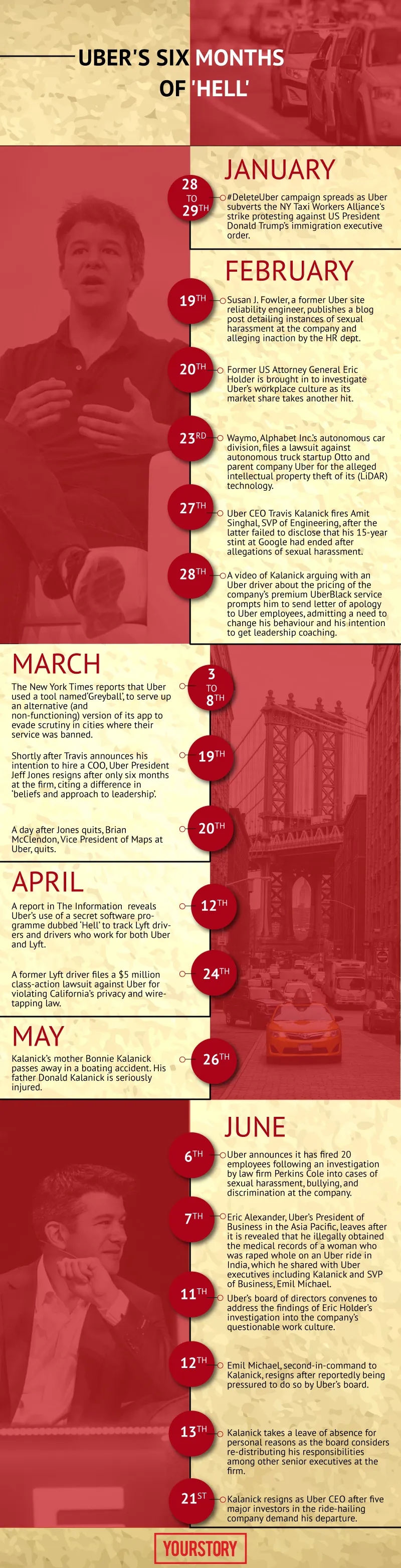

2017 is Uber’s annus horribilis – one that is far from over even with iconic CEO Travis Kalanick departing in the middle of the year.

Key takeaways:

- Uber’s public fallout has been in the making since 2014.

- The early hustling and shifts in the grey areas became breeding grounds for an unethical culture as the company grew.

- Travis Kalanick should’ve made way for a new CEO or COO three years back.

“Necessity taught me the very fine art of bootstrapping. Blood, Sweat and Ramen is what I like to call it. I was always thinking about how to make things ultra-cheap, hyper-efficient while making a good story out of it.”

This is a tale that any entrepreneur would relate to. The great ‘hustle’ of building a product and achieving phenomenal scale. A post by Travis Kalanick in his archived blog, Swooshing, talks of the different ways in which he hustled over 10 years in different companies that he established and sold. These are powerful stories, ones that entrepreneurs find inspiring, mentors yearn to be associated with and investors put money into.

And yet on 13 June, in a letter to Uber employees, while announcing his indefinite leave of absence, he wrote:

“For the last eight years my life has always been about Uber. Recent events have brought home for me that people are more important than work, and that I need to take some time off of the day-to-day to grieve my mother, whom I buried on Friday, to reflect, to work on myself and to focus on building out a world-class leadership team.”

A week later, he succumbed to investor pressure and resigned, leaving behind a whole lot of questions and no real answers about the future of Uber. The CEO of one of the most valuable startups in the world had left with no real line of succession in place. The unicorn, valued at $68 billion, is now going to be run by 14 of its senior executives.

Uber is a mature product with a global presence. It has legions of loyalists, so the brand will sustain, for at least a while. Most investors believe that Uber will put an interim CEO in place before setting out to find a new leader.

The candidates have their work cut out for them because they will need to break the hustle-your-way-through-it-all image that Travis had acquired. In the meantime, what’s left is, as the Wall Street Journal put it, 14 bosses and one corporate Game of Thrones.

Half a world away, we look at the tragic character flaws and circumstances that served up a near-Shakespearean tragedy.

The tipping point?

Was it the #DeleteUber campaign? Was it Susan Fowler’s catastrophic blog post? Was it the Waymo lawsuit? Was it the ‘Hell’ or ‘Greyball’? The medical records saga? What went wrong? Which of these was the tipping point?

Krish Seshadri, who has earlier worked as a senior executive for Facebook and Zynga in the Valley and in India, believes it was a combination of cultural chaos and lack of leadership:

“Legal troubles and business problems are always a part of business. What really went wrong with Uber was the lack of a proper leadership that (should have) built a company solid with cultural values.”

Travis built a successful startup that not only changed the face of personal transportation but also became a force to reckon with while earning a sky-high valuation. When Uber started in 2011, based on an idea that is credited to Co-founder Garrett Camp, Kalanick was exactly the type of leader that the San-Francisco based ride-sharing app needed.

“There are very few startups that can succeed the way Uber has, and there are fewer entrepreneurs who have such a lasting impact on the world. There can be no denying the work he has put in. People in over 600 cities across the world love and use the product,” Kris points out.

Change-maker, rule-breaker

Travis was the driving force behind Uber’s growth. He built the company by pushing people hard, all the time. Given its unique model, he knew that Uber would have to walk a fine line between what was legal and what wasn’t. In defiance of taxi unions, it was making calling a cab a simple experience that put the cab driver in direct touch with the passenger.

Uber was ruthless in the way it got ahead. It reportedly deployed the dubious ‘Greyball’ technology, since 2014 to serve up an alternative (and non-functioning) version of its app. The aim, say, critics, was to avoid legal scrutiny in cities where its service had been banned, including South Korea, China, Australia and parts of the US.

Between 2014 and 2016, Uber is also reported to have used ‘Hell’, a software tool that could track how many of its competitors’ drivers were available for new rides and where. “We needed to get the job done. When you have a large vision, the focus is on ensuring that things get done,” an Uber employee based in the Valley conveyed to YourStory on condition of anonymity.

Did Uber’s sheer size get in the way?

As Garrett wrote in a post on Medium: “…in just 7 years the Uber team has turned a simple idea into one of the fastest growing and impactful companies of all time.”

Today, Uber has 12,000 employees and has branched out into the food delivery business, but this growth has come at a cost. Even as it went global, it had to cede territory and exit China. It remains embroiled in a bitter battle for India and South-East Asia, where the market is valued at $68 billion. Group company Otto, meanwhile, is locked in legal battle with Google’s parent, Alphabet.

Uber has always been focused on the product and on growth, perhaps at the cost of neglecting what makes organisations truly great – their culture. Krishna Kittu Kolluri, Founder and Managing Director, NeoTribe Venture, San Francisco, states that the primary tenets of leadership are culture and communication. Culture is a set of shared values.

“As a leader, you not only have to practice what you preach but also preach what you practice,” he says, adding, “While culture doesn’t guarantee success, a company without culture cannot build a sustainable business.”

And when a company grows that fast but doesn’t establish a strong cultural ethos, a set of micro-cultures begin to develop within the organisation. A woman engineer in the tech community in the Valley says,

“Sexism and a toxic culture in the startups in the Valley isn’t unheard of. The problem is the fact that it is considered the right way to grow. Drawing lines is a problem in many cases.”

Great product but not a great organisation to work for

Says Kris,

“Uber built a great product but a lousy, dysfunctional organisation. When internet startups blitz scale building high performing teams, they miss out the fact that organisations are more than just building great products and require the right people who can build those skills. It needs mature people who have leadership skills. Someone who can listen, learn and grow and also have mature founders who know what they can and can’t do.”

Garrett has agreed that they neglected parts of their culture as they focussed on growth. “We have failed to build some of the systems that every company needs to scale successfully,” he explained in the blog post.

After the video of Travis’s row with an Uber driver went viral, he acknowledged that he needed to grow up. But that wasn’t the problem. The problem was: why had it taken so long to acknowledge it? Several insiders have said that Travis stayed on longer than he should have, and in doing so, strongly moulded the company in his image. Breaking that image is now a challenge for anyone.

The curse of the founder as CEO

“Many are great tech guys and brilliant innovators, but lack the necessary emotional quotient and maturity that is needed to deal with people. They hustled and built the product and think that they can continue to hustle and make it grow,” says Kittu

Adds Kris, “Companies often grow rapidly with a hustler at the helm. But in many such cases, founders lack the expertise to manage a global business.”

What is surprising, though, is the fact that investors waited so long to address these issues. Kittu adds that this is a common enough problem with most first-time entrepreneurs. He says,

“Every year, the job on-ground changes drastically for founders. In Uber’s case, the company was growing at a phenomenal rate but many founders, like Travis, don’t reinvent themselves. In anything new that you learn, you have a coach. But in the startup ecosystem, there isn’t any training or coaching, or mentorship or tutelage. And that is because many people at the board level, in the venture capital area, even in the Valley, haven’t built large companies either. So nobody knows how to build culturally attuned leaders.”

Even though Uber isn’t Travis’s first startup, his earlier companies never grew to the scale that Uber did. At Red Swoosh, he didn’t have to manage a team that comprised global heads, people from different cultural backgrounds and people of different skill levels.

In the Valley, successful startups have often been scaled successfully because they have brought in a CEO or COO at the right time. Google, in consultation with its investors, hired Eric Schmidt as CEO when it was less than two years old and had just 150 employees. Facebook got Sheryl Sandberg as COO when Facebook had 800-odd employees in year four.

Kris adds, “There has been a tried-and-tested model in the Valley where mature, experienced execs from outside are brought in early as CEO/COOs to partner with the brilliant product/tech founders. In many cases, tech founders have little interest or skill in organisation building or the business side of things. They focus on overall strategic direction, product vision and technology. Outside executives focus on building the org, sales, marketing, ops, BD, HR and culture.”

Professional executives provide strong leadership metrics to the team. In the case of both Google and Facebook, these executives helped scale the organisation and keep it nimble while shaping organisation culture and values.

Leadership and training were key components of these growth plans even as the companies focused on putting processes in place, building robust global systems and bringing in fiscal discipline. The founders in both cases were mature enough to understand that they need to step back.

Uber did not follow this model. And as one investor pointed out, its founders emulated the wrong ideals. Travis had always relied on a close-knit group of confidants – a coterie of Uber’s top executives who were among some of the company’s earliest employees. They all shared Travis’s aggressive sensibilities, and the lack of diversity only got in the way of the organisation’s evolution.

“For many of my colleagues and friends, the idea of joining Uber was a dicey one. While the product seemed great and awesome, the company felt closed. The culture seemed driven strongly by what Travis did and felt,” says an entrepreneur in the Valley.

Adds Kris, “What is surprising is that Valley VCs who are so astute in understanding what is happening didn’t push Kalanick earlier on for an external CEO three years back when it was still small. Without leadership and an unrestrained, broken culture, Uber and its CEO got into constant trouble.”

A lesson for all

“This problem isn’t just something that Valley companies face; it is the same for several Indian startups too,” adds Kittu. There is a need to learn to draw a line and find a balance. Founders may never realise that there is a problem as they are too close to the situation. The push needs to come from outside.

Uber today has become synonymous with a toxic ‘bro culture’, and is perceived as arrogant about everything it has achieved and the methods it has deployed to get to where it is today.

The way forward is a transformation of company culture, starting with appointing a CEO who can consolidate the company’s growth and build out a team that can guide Uber to achieve the lofty goals it had set for itself.

Investors have realised that they stand to lose billions of dollars if the company’s valuation falls. Travis, though, might have to either stay away from the new CEO or function as the product visionary who has a seat on the board and will direct the new CEO in one way or another.

Either way, it’s like Garrett wrote:

“…what matters now is that we know what needs to be changed. We must update our core values, listen better to employees and riders, and prioritise our drivers. The team at Uber has some of the best problem-solvers in the world, and we must now apply our talents to solving these issues through clear actions.”