The seven sins of Snapdeal: how and where they lost their way

E-commerce is yet to make money in India. But the consolidation season has already begun. For Snapdeal, was it long coming?

In an earlier interaction with YourStory, Snapdeal Co-founder and CEO Kunal Bahl had said that the company would announce something new every week. And it seemed true for a long time—until a few months ago. Despite the launch of innovative ideas, acquisition of numerous promising startups, and the rebranding campaign that cost the SoftBank-backed company Rs 200 crore last year, Snapdeal seems to have accepted defeat.

Unless you have been living under a rock for the past few months, you already know that Snapdeal is about to be acquired by its former rival and e-commerce market leader Flipkart. The only details that remain undisclosed are when and for how much the deal with Flipkart will be closed. YourStory looks back at where the seven-year-old company lost its way, and how.

- No differentiation

Busy building too many warehouses and burning cash, Snapdeal never built any category as their USP like Flipkart did with fashion and electronics, and Amazon with Prime and Pantry.

“Snapdeal was not doing anything ground-breaking. Online retail, after all, is also just retail. Your competitors are as good as or better than you. If you don’t have a striking differentiation, why should a consumer choose you over the others? Snapdeal failed to stand out—they had the upper hand in no particular category or service,” says an e-commerce expert who does not want to be named.

Additionally, Snapdeal’s tie-ups with ClearTrip, redBus, Zomato, and UrbanClap for their respective services also failed to make any impact.

2. Acquisitions for nothing

Many of Snapdeal’s acquisitions turned out to end poorly. The exception is logistics firm GoJavas; but Snapdeal failed to capitalise it long term, and it fell into the hands of Pigeon Express despite Snapdeal's 20 million investment in it. Snapdeal's own logistics arm Vulcan Express was also rumoured to be in talks for sale.

If Flipkart acquired Jabong and eBay India on their deathbeds, every company Snapdeal acquired was at its peak. But as fate (or bad administration) would have it, Snapdeal’s acquisition of FreeCharge also failed to make waves for the company, as Paytm continued to be the leader in digital payments and FreeCharge failed to capitalise on demonetisation like Paytm. FreeCharge is now rumoured to be close to acquisition by Paytm.

Snapdeal could have had the upper hand in fashion, a high-margin category, had it acquired Jabong. In fact, after Flipkart-owned Myntra acquired it, Snapdeal had tried acquiring affordable fashion marketplace Voonik and luxury e-commerce platform Zapyle—according to sources with direct knowledge of the talks—but failed to take the talks to a serious level. (Snapdeal has denied this when asked for comment.)

Snapdeal’s earlier acquisition of Exclusively.com, for luxury fashion, bombed in less than a year and was shut down a few months ago.

3. Omnichannel downfall

The failure of Snapdeal’s omnichannel strategy stands out in its list of downfalls. When it was launched in October 2015, many experts saw it as a possible game changer for Snapdeal. Organised retail in the country itself is becoming increasingly omnichannel, with conglomerates like Tata (with TataCliq) hopping onto the e-commerce bandwagon. It had promised that customers can discover products online and order with faster hyper-local fulfilment executed by offline retailers.

It also lets users to access value added services including demonstration, installation, activation or returns at a store near them. Importantly, with this customers will be able to procure products within two hours of ordering and access these services at the nearest store if they chose the pickup option across 70 cities in India. (This service was not available for cash-on-delivery purchases.)

This model had great potential—with initial tie-ups with Mobile Store, Shoppers Stop, etc. With efficient implementation, it could have given Snapdeal a turnaround, but failed to make waves due to strategic mismanagement.

A former senior executive at Snapdeal tells YourStory that the omnichannel team had faced chaos inside the organisation. “The leadership team had little power. They were unable to resource it to culmination because it needed a dedicated tech team of engineers which it was not provided with.”

On the other hand, may be the time was not perfect for this launch. To provide touch and feel as well as lesser delivery time for the customer, all parts of the system should work out. If offline retailers are not fast for pick up, the whole system can collapse. Yet, Snapdeal was able to reduce returns from over 10 percent to minimal for large electronics with this initiative, according to the person mentioned above. Its supply chain costs were also cut by one-third at the pilot level.

“Around Rs 10 crore only was invested in it since it was a low-key effort. But it needed creative partnerships and technology hacks. For inventory in offline network, they used order fulfillment software Unicommerce. But it stuck on the main tier-1 Snapdeal stack. Every time an update happened, the Unicommerce system went for a toss as it was not well integrated. Net promoter score (NPS) in those categories went up to 25–50 percent. Customer experience bettered while delivery time decreased; costs were minimal as return was almost zero,” says the senior executive. But due to “egos at play,” this person adds, there was no collaboration between the technology and business, and the opportunity was lost.

- No thought for grocery and furniture

- These are opportunities Snapdeal lost out on. Both grocery and furniture categories have not been cracked yet in Indian ecommerce. Even Flipkart is only building on those now. (Amazon has been quietly building its kirana network and Amazon Pantry, and was reportedly in talks with online grocery market leader Big Basket for its acquisition.)

Supply chains work very differently for grocery than they do for other items; but Snapdeal had GoJavas—one logistics firm which experts swear by. The Delhi-NCR region could have been a great place to pilot, say experts, as Grofers - which currently has an upper hand- started only in late 2013.

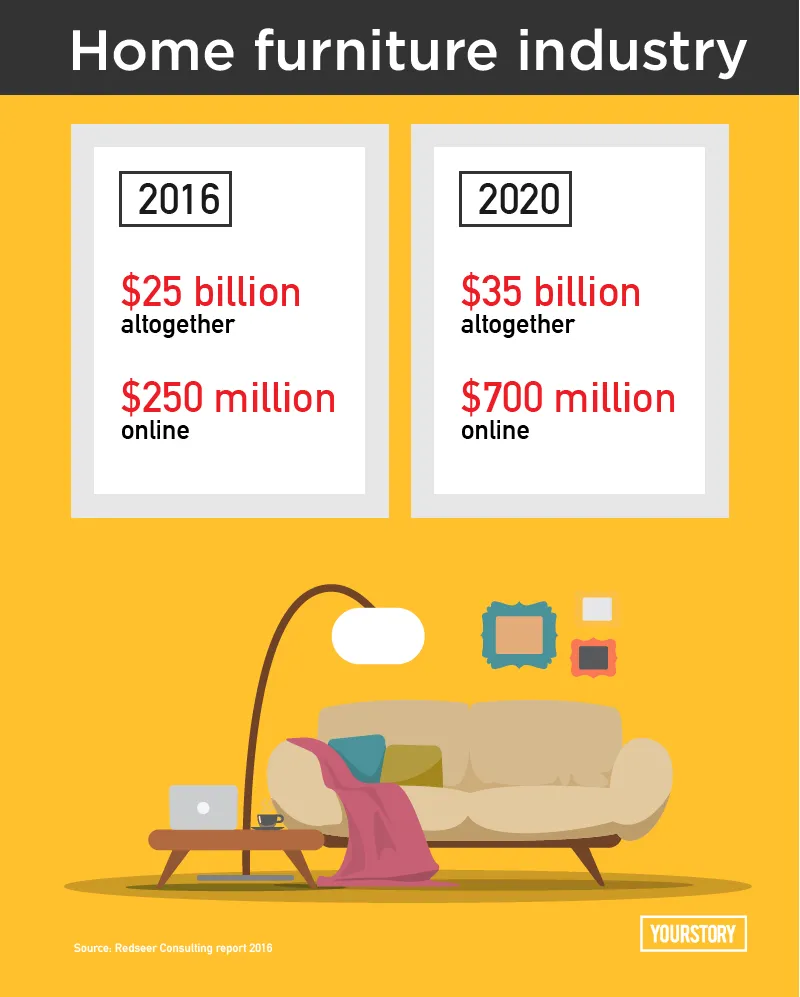

Snapdeal also had the highest number of fulfilment centres for any online retail platform in the country—69 across 25 cities, while Amazon currently has 27 and Flipkart 26. This could have been a major strength had they attempted to push the furniture category—one which demands impeccable logistics due to the possibility of damage. Also, Snapdeal being based in Gurgaon had an advantage considering the fact that the furniture manufacturing industry is concentrated in the Rajasthan belt. The category is yet to make profit; but there is no denying that it is one of the highest margin categories, and the online market is nowhere near saturation.

- Lack of democracy

It’s not the money or brand, but culture that inspires your team members to work hard. But in Snapdeal’s case, sources say, this was lacking. “Co-founders Kunal Bahl and Rohit Bansal never allowed others to participate in decisions or shares. Many senior officials left Snapdeal—even those with five years of experience there—due to the autocratic structure within the organisation,” a former senior employee says on the condition of anonymity.

According to this person, the money was not shared with anyone—not even the exit money, which was promised to the leaving employees. “The founders took it all. In contrast, Flipkart is more democratic and inclusive. Snapdeal was never bothered about building a culture; it never focused on its people,” says this person.

Rohit and Kunal, before taking the 100 percent salary cut, were both reportedly drawing an annual salary of Rs 46 crore. An investor who has closely observed the industry says Snapdeal had no commendable secondary management team. “Long-term planning was not something Snapdeal did best. Besides Kunal and Rohit, there was no major executive who could lead the company, like Kalyan Krishnamurthy could do for Flipkart,” says this person. (Anand Chandrasekharan, who was hired as CPO from Silicon Valley, left the company a year after joining.)

6. No golden touch

'Snapdeal Gold'—the free service that needs no registration—followed the launch of Amazon Prime, which charges Rs 499 annually. Under this offer, the customer can get next-day free delivery in select areas, and standard free delivery everywhere else. Also, returns can be made in 14 days instead of the usual seven days. Orders placed with cash-on-delivery do not get this offer.

But alas! Customers wanted a better experience, not just fast delivery. Snapdeal claims that this service was aggressively pushed following demonetisation last year, and now more than 20 percent of the order volume at Snapdeal is shipped through Snapdeal Gold. However, that metric does not look great when compared to Amazon Prime's. Amazon claims that one in every three orders placed on its platform is from Prime customers, despite being a paid service.

7. Multilingual tragedy

The vernacular app was lauded at the time of launching. However, either rural India was not ready for e-commerce or vernacular was not the most effective way to reach out to the masses. Those masses know how to transact – they figure it out even without the regional language on the app. So there was no volume of users to cater to with the 14 regional languages in the app. Moreover, the regional audience has to be much larger in number for such an initiative to succeed.

Language was, in fact, never the biggest issue to be solved to expand the customer base for e-commerce. The entire shopping experience from UX to products to delivery needs to be fine-tuned according to the needs of this demographic.

End of the story

It is said that when the going gets tough, the tough get going. But this Unicorn has lost its zest, and cannot charge forward anymore—too many initiatives and not following through have resulted in its downfall. Despite some interesting innovations and services, Snapdeal was not able to create an offering the customer could not live without.

However, in their official statement, Snapdeal says: “At various points in time, focused initiatives are conceptualised and implemented for specific business objectives relating to customer experience, unit economics, operational efficiencies, etc. These are tested for consumer response, ecosystem readiness, and business benefits. Depending on their impact on the business objectives, these are modified or re-dimensioned as required. The tech build out of these initiatives remains available for future use, as per evolving market requirements.”

If e-commerce is to see consolidation, Snapdeal’s acquisition will be the first big event to lead the way. In fact, this acquisition can give a fresh lease of life to Snapdeal. After all, Jabong gained positive unit economics after it was acquired by the Flipkart-Myntra alliance. The founders (and existing investor Nexus Venture Partners) pouring in Rs.113 crore in a surprise move also shows that the stakeholders have not lost all hope yet.

For the growth of any industry, a majority of players have to die down–just like the theory of ‘Survival of the Fittest’. But the positive momentum that comes with this wave can create more players, bring in more money, and give way to more innovation.