Dear students, your success is not defined by board exam marks

Every year lakhs of students are made to believe that the board examination is the first step towards an individual’s successful life.

Speaking about the Indian education system TV Mohandas Pai, Chairman of Manipal Global Education Services, says,

Formal education remained the realm of the few for centuries while the bulk of economic output was driven by human labour.

The month of May each year begins and ends on an anxious note. This year, this fateful month is set to decide the “future” of nearly 22,36,268 students who have taken the much-dreaded 10th and 12th board exams across the Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE), Sate boards, Indian Certificate of Secondary Education Examination (ICSE), and Indian School Certificate Examination (ISC).

The preparation and stress surrounding these exams are now garnering responses from MNCs and knowledge ‘tuition’ centres as well. Be it the ‘Utterly Butterly’ Amul girl with Amul Memory Milk which aims to boost memory power, BYJU’s Your Learning mobile application, or magical pens that promise to make students succeed in their exams— board exams have become a medium for commercialisation.

Soujanya Ganig, National Program Coordinator for Mission Possible at World Federation of United Nations Associations (WFUNA), says,

We need to make liberal education the norm and not the exception— so that along with benefiting from an interdisciplinary education, students are also under less pressure to make crucial life decisions at 15.

Parents, students, and teachers across India invest their time, money, and energy towards this “important phase of life.” Hence, it becomes imperative to understand what makes this certification so stressful and at the same time question if the hype and brouhaha surrounding it is worth it.

Entering the hall of stress

As he enters the 10th grade, Shravan Gupta wonders why his extracurricular activities and sports time have suddenly been cut short.

My recess time is now converted to study period and everyone just talks about the big board exams which are headed my way. I don’t know what happened. Cricket helps me calm down. I just finished ninth grade, he says.

Vasanthi Hariprakash, a former journalist and a guest lecturer in media studies, was surprised to see that her son stopped going for his football classes when he entered the 10th grade. In reply Anirudh, her son, said,

Amma, my friends’ parents stopped sending them for football practice. So, who do I play with?

The lack of warning and preparation, combined with a change in attitude from parents, teachers, and well-wishers often takes a toll on the adolescent mind. "To escape this stress, students might also indulge in activities which give them instant gratification such as drugs, alcohol, and sex at an age where they don't have the maturity to deal with them", says Gurekta Sethi, a former teacher at Oakridge International School, Bengaluru.

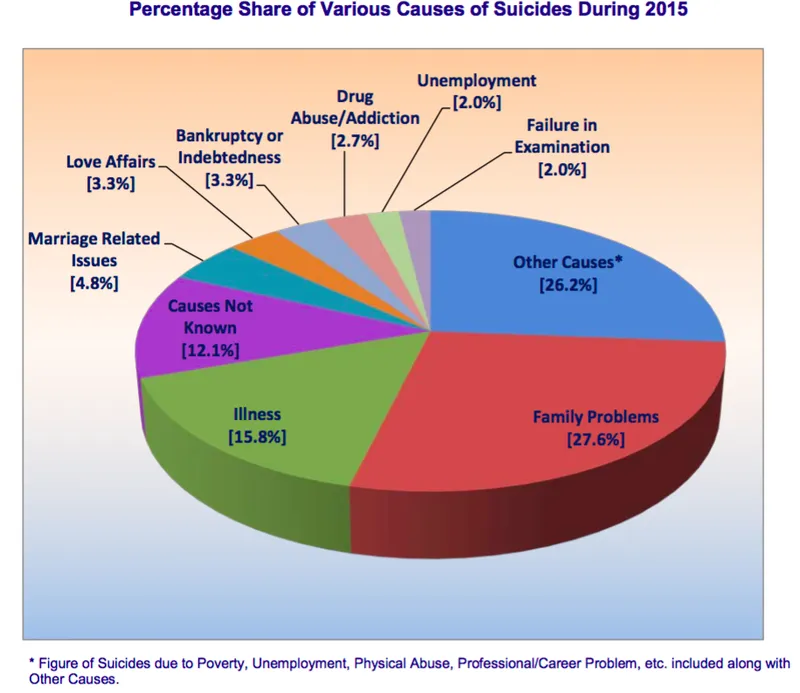

India has one of the world’s highest suicide rates amongst youth aged between 15 and 29 years. The National Crime Records Bureau 2015 report shows that an alarming 15 suicides took place every one hour across the country and the number of student suicides stood at 8,934.

The pressure on students affects their emotional status as their self-worth is measured according to their grades, Gurekta explains. Tuitions and the coveted seat in top colleges add to their already burdened school bag-carrying shoulders.

Grades and marks do not define your future

The Indian education system requires a student to decide his/her respective field of interests at two varying stages. Post the 10th grade the average 15-year-old child is expected to choose primarily between three subjects— science, commerce, or humanities— which two years later become the stepping stone towards a prospective career path.

The phase becomes difficult for the young adult primarily because of the lack of exposure and effective guidance available to the student body. "Most students are clueless as to what to do and where to get in. Children’s interest level is often restricted to either engineering or medicine," says Nimmy George, a child psychologist and student counsellor.

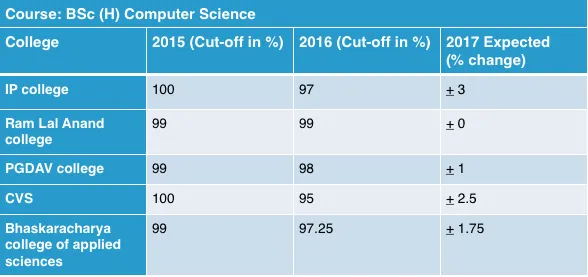

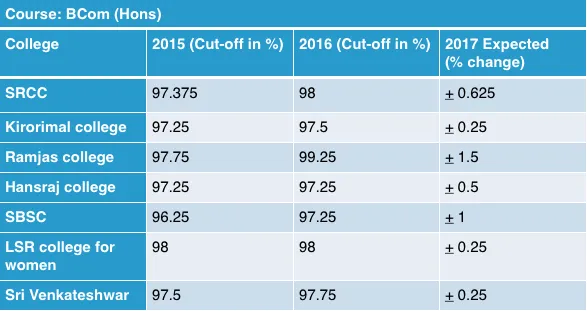

Further, college cut-off percentages in the recent past have not been encouraging either. In the past few years Delhi University, among others, has seen 100 percent cut-offs in several subjects, thereby setting an almost impossible standard of achievement for students to be considered for a merit seat.

With an aim to tackle this unreasonably high cut-off requirement which was leading to inflation of marks by several boards of examination, the Government of India passed a judgement discontinuing the “moderation” policy. This judgement disallowed CBSE, CICSE, and 31 other boards across the country to tweak the marks of students to bring uniformity in the evaluation process, such that someone who scored 85- and another student who scored 90-marks were both given a final average score of 95.

If students fail to perform in their boards or standardised exams, the management quota or donation seats are the only other option available for them to get into their dream colleges. However, Anirudh braved the odds and decided to take a year’s gap to get through his dream course and college on merit alone.

"I was relieved that he wanted to get into his college on his own terms. But is a gap year really a 'big deal'?" Vasanthi questions.

Prof MV Rajeev Gowda, Member of Parliamentary Standing Committee on Human Resource Development, says,

Different people mature at different paces and we need to support our youth as they grow and develop. We need to ensure that they do not see themselves as failures if they don't top in 12th or college. We should encourage them to learn more about their aptitude, to experiment and discover their interests and passions, and to always invest in self-development.

Education 3.0: shift to quality rather than quantity

The cut-off percentages are only the tip of a very dangerous iceberg. “We need to address a host of other issues like our obsession with high-stakes testing, institutionalisation of rote learning, and the culture of competition in learning. We need to move from an approach of recall to one of conceptual application—we need a system that is pedagogically designed to nurture students’ multiple intelligences,” says Soujanya.

The current education model solved the problem of scale; through legislations, education was available to the masses, but it failed to maintain the quality needed, Pai explains.

Education 2.0 prioritised literacy and recall over problem-solving and curiosity-driven exploration.

Hence, Pai advocates for Education 3.0, which focuses on quality at scale with technology as the lever. Tech-enabled pedagogical models to enhance formal education can be unleashed at scale by innovative companies.

We must help students become problem-solvers rather than information assimilators. Technology can drive our education system to become the force multiplier to create an innovative future-ready India.

In India, education is equated with social prestige and a child’s college career is a family decision rather than a unilateral choice. Apart from the social pressure, the child goes through a psychologically tough period due to the competitive nature of examinations. Can we not discuss another narrative where students are not made to believe that there is only a set pattern in life—college followed by career?