How wars, ethnic violence, and global apathy are pushing 20 million people into famine

A man-made famine, stemming from rapacious power struggles, is threatening the lives of 20 million innocent civilians, including 1.4 million children. The international community’s response remains fatally slow, leaving the people to the fate of an entirely avoidable disaster.

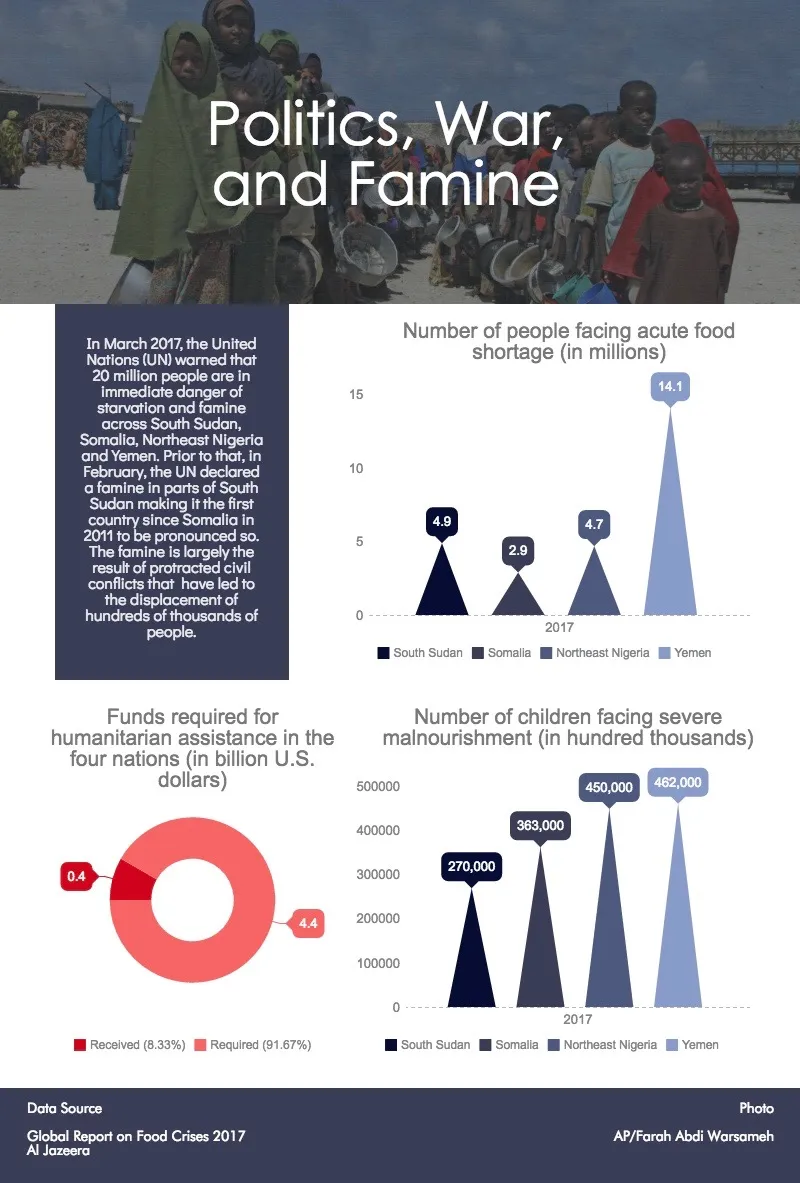

The United Nations (UN) defines famine as a crisis where at least 20 percent of a region’s population does not have sufficient food to be healthy, more than 30 percent of children under the age of five are severely malnourished, and two in 10,000 people or four in 10,000 children die due to extreme hunger every day. Presently, 20 million people, including 1.4 million children, are inching closer to this state of living as the spectre of famine looms large over South Sudan, Somalia, Northeast Nigeria, and Yemen. In South Sudan, where famine has already been declared in parts of Unity state, 1,00,000 people are facing starvation, while one million more are on the brink.

The UN is poised for immediate action but is gravely restricted by the lack of funding. The organisation is in need of $4.4 billion to provide humanitarian assistance across the four nations but, as of March, less than 10 percent of the required capital had been received. However, even with sufficient capital, aid workers would still not be able to reach all the people in need.

With the exception of Somalia, where crops and animals have perished due to consecutive droughts, the remaining three countries are on the verge of an entirely preventable famine resulting from prolonged civil conflicts. Internal displacement, soaring food prices, and destruction of fertile land have made it impossible for people to produce or buy food, or even access water. The situation is worsened by the spread of diseases such as diarrhoea, cholera, and measles, against which the acutely malnourished have no resistance.

Warring parties, including governments, continue to block relief to several affected regions using different tactics. While the threat of violence dissuades aid workers from entering certain areas to begin with, theft of supplies or long lists of permits prevent much-needed aid from reaching civilians where possible. The Government of South Sudan is said to be deliberately obstructing aid to starving people in rebel-held areas as a war tactic. Residents in many villages have been reduced to eating grass, water lilies, and insects to survive.

This man-made famine, stemming from rapacious power struggles, is threatening the lives of innocent civilians, especially children, who, even if they survive, are likely to be mentally or physically stunted for the rest of their lives. The UN’s ringing appeals for donations from the international community might produce enough funds to save those in immediate danger, but the larger problem of food insecurity in these regions can only be solved by conflict resolution. Otherwise, their citizens will time and again be on the threshold of crippling food shortages and impending death.

Political and ethnic divide in the world’s newest country

A mere two years after its independence from Sudan in 2011, conflict broke out between the President and the Vice President of South Sudan, soon erupting into violence along ethnic lines. In 2013, President Salva Kiir, belonging to the ethnic tribe of Dinka, fired his Vice-President, Riek Machar, an ethnic Nuer, effectively splintering the governing Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A).

The Dinka and Nuer tribes have historically clashed with each other over land and other resources, but put aside their differences in the fight for liberty from Sudan. But the united front didn’t sustain for long. Machar started to openly criticise Kiir’s policies and vowed to contest for presidency in the next election, an act which eventually led to his firing. The immediate cause of clashes is still a matter of debate. While some say that Kiir’s public accusation of Machar’s involvement in a plot against him sparked the violence, others attribute it to the attempt by the presidential guards belonging to the Dinka tribe to disarm those of the Nuer tribe.

Opposing factions started looting, raping, and killing people of rival ethnicities in the subsequent battle for power and oil. To make matters worse, President Kiir’s order to redraw internal boundaries set off more conflicts over the control of land between citizens and earned his government as well as the Dinka tribe the enmity of another tribal group known as the Equatorians. However, the ethnic dimension is only one part of the conflict. Both Kiir and Machar have notable supporters among the opposite ethnic groups, for this is largely a political struggle where loyalties change based on whose policies benefit someone’s self-interests the most, notwithstanding their ethnicity.

Since the start of the conflict, 50,000 people have been killed, 2.3 million people have been displaced, and nearly five million people are experiencing acute food shortage. Calls for an arms embargo and an armed intervention in South Sudan by some members of the UN Security Council both came to naught. On ground, the government’s soldiers themselves are stealing food meant for relief or demanding bribes from aid workers.

Famine shadows Somalia once more

The last time a famine was declared was in Somalia in 2011, when 2,60,000 people died, half of whom were children. Despite alerts from the Famine Early Warnings Systems Network (FEWS-NET), the international community scrambled to act only after famine was announced a year later and several people had already died. Similar to the present situation, the country experienced severe drought that left its crops and livestock dead, while food prices inflated due to a fall in production.

But the difference is that, last time around, the Islamist outfit Al-Shabaab was at large in the country. The group, which wanted the installation of an Islamic state, was at war with the government and refused to allow people to leave drought-hit villages for food and water, while at the same time preventing foreign aid from entering the regions. Though Al-Shabaab’s presence continues in Somalia, defeated by government and African Union forces, it has lost much of its stronghold. However, the severely affected areas are those still under the control of the group in the rural south.

Somalia’s food shortage is more to do with climate change than conflict. It is true that the country is struggling to cope in the aftermath of its protracted civil war, and that fighting between the government and Al-Shabaab persists in several areas. But the probability of aid reaching people in need is far higher in Somalia than the other three countries, for conflict here has (relatively) subsided. Even Al-Shabaab, though restricting foreign aid as before, is said to be permitting freer movement of people looking for sustenance.

Boko Haram’s reign of terror in Northeast Nigeria

Boko Haram, whose official name literally translates to “People Committed to the Propagation of the Prophet’s Teaching and Jihad,” has been terrorising northern Nigeria since 2009 and waging a war against the Nigerian government which, in its view, is run by “non-believers.” Formed in 2002 as an opposition to Western education, its founder set up a mosque and an Islamic school in Maiduguri, the capital of Borno state. However, the school soon became a turf for recruiting young fighters for the group’s larger political agenda of an Islamic state.

It has attacked government buildings, politicians, preachers of Christianity, even Muslim clerics following different traditions, killed and looted villagers, abducted women and children, forcefully enlisted men and young boys, enslaved schoolgirls, and displaced 2.6 million people. Fertile land has either become inaccessible or been destroyed. Those who escaped live in camps, depending upon the little food and medical aid they receive, while two million people cannot be reached for assistance as they still live in villages and towns controlled by the outfit. Though the Western-backed Nigerian military has been liberating villages and towns from Boko Haram, the group still remains relatively powerful.

It took a long time to gauge the true extent of the food emergency in the country, as a majority of the areas were dangerous for humanitarians to enter. According to the Washington Post, some aid workers believe that the state of Borno already experienced bouts of famine, or already is in one. The Nigerian government’s refusal to acknowledge the dire situation and seek foreign help only escalated the crisis. The consequence is that 4.7 million people are in critical need of food, while 4,50,000 children are severely malnourished, 75,000 of whom are at the risk of dying in coming months.

Civil war paralyses the poorest Middle Eastern nation

Yemen spiralled into conflict in 2015 after Houthi rebels, members of the country’s Zaidi Shia religious-political movement, captured the Presidential palace in the capital city of Sanaa. The Houthis found supporters in regular citizens, including Sunnis, who were losing faith in President Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi’s government as well as military forces still loyal to former authoritarian leader Ali Abdullah Saleh.

Fearing the group’s rise to power and suspecting it of being backed by Iran, Saudi Arabia and eight other predominantly Sunni Arab nations formed a coalition supported by the US, the UK, and France to carry out air strikes and keep the internationally recognised Hadi government in power. The war has destroyed Yemen’s economy and infrastructure, displacing more than 2.4 million people and killing over 10,000 civilians. People are without food, water, sanitation, and basic medical services, especially the ones that stay behind in their towns and villages.

Agricultural lands and food transport vehicles and channels have repeatedly been targeted by coalition forces, increasing the vulnerability of civilians to famine. Yemen imports close to 90 percent of its food, a majority of which comes through the Hodeida port, currently under the control of Houthi forces. However, Saudi ships have been blocking entry into the port citing the risk of arms smuggling, despite assurances of supplies inspection on arrival by the UN. There are even rumours of the Saudi-led coalition planning attacks on the port, which is the best option to bring in food aid to the country. The coalition’s Western allies can pull out of the alliance or pressure Saudi Arabia to ensure delivery of aid as well as to hold peace talks. However, there seems to be no sign of either option materialising. In fact, the US is getting more deeply involved in the conflict while at the same time pushing for enormous cuts to its foreign aid budget.