Why we need to look beyond Trump’s 'nastywoman' insult

“How are you dealing with the elections in Washington?” a friend asked me earlier this week. “Nothing new,” I explained, “It’s finally out in the open.”

My tone is one of hope, not defeat. The 2016 US Presidential election has unwittingly become the malady of our time. Election talk is tiring—shameless slander and demagoguery in public discourse aren't easy to digest—but let’s admit it:

Donald Trump’s year-long campaign has single-handedly pulled the rug from under our feet and forced us to question troubling platitudes in conversations around gender. Not just in the United States, but world over.

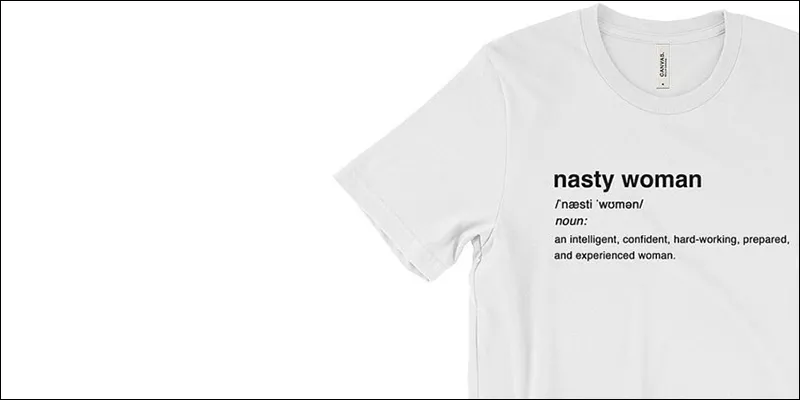

No sooner had the final Presidential debate concluded than Twitterati flooded the site with GIFs, memes and hashtags humorously challenging Trump’s churlish insult of Hillary Clinton: a “Nasty Woman.” Google Ghost even went so far as to create a pink and white T-shirt with ‘Nasty Woman’ plastered on a giant heart to direct funds towards Planned Parenthood, an organisation that provides reproductive health services for millions of Americans. The #NastyWoman insult, one publication claimed, has now become the rallying cry for women everywhere.

Indeed, it has. There’s no arguing with that. But dig deeper, and there’s a larger issue at play.

The struggle, some feel, is that topics like misogyny, patriotism and racism have suddenly resurfaced from the corner of those ‘feminist-activist-type’ websites, and disturbed that quiet comfort of prejudice. But the truth is these beliefs have been carefully cultivated over time. They are by no means a Trump creation. My personal favourites:

"I have nothing against Muslims, but I won’t marry a Muslim. I’m all for women’s rights but I’m not a feminist. I’m not homophobic, being gay is just a sin that’s all. Women should definitely work but those career-oriented types who don’t like babies are weird. I don’t care about skin colour but I just don’t want to be 'too dark'.”

Who have we heard say these words? Most likely aunts, uncles, parents, friends or people we know—perhaps even we’ve said it. So, while Trump’s divisive and rhetoric is inherently dangerous, the words he uses should hardly surprise us.

Discrimination has thrived over centuries and it has taken more than one #NastyWoman to check it. Examples surface around us every day. In Delhi, it took the courage of a collective band of feisty college girls to fight sexist University policies. When Shobaa De, socialite and writer, made a remark shaming Kate Middleton’s body, it was a 19-year-old college student that called her out. In Argentina, thousands of women took to the streets to protest the brutal rape and torture of 16-year-old Lucia Perez. In Poland, nearly 24,000 men and women brought the country to a grinding halt to protest a sweeping abortion ban.

Making sense of gender narratives or ‘smashing patriarchy’ isn’t as simple as web articles, Facebook statuses and twitter chats make it seem. It is hard. It takes tough, difficult conversations. It involves arguments with people we love and care about. It takes courage to challenge our own biases.

It takes will to test our own ability to fully embrace differences in each other. It takes perseverance and patience to understand different perspectives. Most often, it means failing—over and over again.

Sometime in 2005 or 2006, when I sat in the audience of NDTV’s 'We The People' watching Barkha Dutt question spokeswomen from the Congress and BJP about Anna University’s dress code controversy, I wondered why some women fought against the rights of other women. Now, watching Scottie Nell Hughes or Katrina Pearson defend anti-black violence or pander dangerous myths about abortion, I still find myself searching for answers.

The truth is, it’s far easier to apply that familiar script of patriarchy and misogyny to point out Trump’s faults, it’s harder to have that conversation about chauvinism and misogyny in women.

Earlier this year, a poll claimed that Trump is nearly as popular with Republican women as he is with men. Even if one were to apply the facile argument that the root of these beliefs stem from patriarchal thinking, it is a mystery why well-educated women who grew up in secular, liberal social environments harbour such thoughts. So the real test is not only to challenge and change men who think like Trump, it is to have a dialogue with women who agree with him.

In some bizarre way, the Trump campaign has sown the seeds for a difficult dialogue. In today’s heated political environment, this is an incredible opportunity for us to turn off the TV, log off the internet and talk to each other. Twitter hashtags and fun T-shirts, that’s the easy part. Try coffee and conversation, that’s way harder.

But more fulfilling.