Last month, I accompanied Kalaari Capital, one of India’s leading VC firms, as a Chinese translator and an intern on the firm’s first trip to China. We heard about how the best of China’s VCs and large companies believe that the Indian and Chinese tech ecosystems will interact in the coming years. Here, I discuss five salient observations from our trip.

Growing up in India, China always felt many miles farther away in spirit than in distance ‑ the Himalayas rising like a fort to separate the two. That illusion broke for me in 2014, when I took a gap year between my third and fourth year of undergrad in computer science to spend a year in China working, improving my Chinese, and backpacking with three pairs of clothes and little else through almost every province in the country. Near Guangzhou, I discovered a Parsi cemetery of the 19th century opium traders from Mumbai. In Beijing, I discovered the long history of imperial exams that in spirit continues to this day, and because of which modern-day Chinese students find empathy for their woes in 3 Idiots. In Xi’an, I met an Indian restauranteur seeking opportunity in the city where the Silk Road began, where Indians had sought similar opportunity thousands of years earlier.

Spending that year at the intersection of history and modernity, discovering forgotten interactions between China and India, helped me evaluate the claims about the future that I came across in the boardrooms of China with Kalaari. In this article, I will evaluate five salient claims with an eye to history and data.

- India is just x years behind China

On our first day in Shanghai, we walked into a 35th floor conference room overlooking a landscape of skyscrapers rising above layers of flyovers. “I could never imagine India like this,” someone said, to which the Chinese VC we were meeting responded, “China was not always like this. India is just 10 years behind.”

Claims that India is closely tailing China were repeated at almost every meeting. We told the CEO of Liweijia, a Chinese online furniture platform, that in India, traditional carpenters are the primary competition to online kitchen sellers like Urban Ladder. His response: “China was like that in the ‘80s or ‘90s, before local factories and distribution networks developed.”

When we met Alibaba, we were told that in the company’s early years, 80 percent of users didn’t have credit cards, an escrow system had to be created to ensure trust, and mobile payments had to be solved. India faces these same problems today, around 12 years after Alipay’s inception.

Behind claims like “India is just 10 years behind,” it is subtly implied, “In 10 years, India will be like China.” Many Chinese investors are betting on this by investing in Indian businesses that allow them to transfer their knowledge of what worked in China to the Indian context.

For example, after Snapdeal’s first visit to China, the company learned more about the Alibaba model from Chinese investors, and decided to adopt it by dropping its original Groupon model. One high-profile investor in Beijing had made four trips to India and was actively pursuing investments into Indian companies that matched his own Chinese portfolio companies. Large Chinese companies are also making strategic investments into their Indian equivalents ‑ Alibaba invested into Paytm and Snapdeal, Didi Kuaidi into Ola, and Ctrip into Makemytrip.

An investor in Beijing even told us that he believes it might be possible to systematically transfer business models that do well in China over some fixed period of time to India. They had tested this successfully in Southeast Asia by investing in a mobile gaming business two years after its model had worked well in China.

Yet the same investor also expressed scepticism that India could develop similarly to China, questioning how a political system that brings competing parties in and out of power every few years could see through large-scale, decade-long projects, like building infrastructure and improving education. While many investors were optimistic about India’s development, and had already started taking exploratory trips to India, some were still critical of the global obsession with pairing China and India.

Claims that India follows close behind China are often justified with cherry-picked pieces of history like “China’s reform and opening was in 1978, India’s was in 1991. India is roughly 10 years behind.” At a slightly more granular level, the differences become stark. A careful historical analysis of the claim that India is 10 years behind China will follow in the next column.

- Manufacturing, money, and materialism

On our last night in Hong Kong, Kalaari hosted a dinner for friends who had helped put the trip together. At some point, the CEO of an online travel portal noted that Indians just don’t spend on international vacations like the Chinese. A few minutes into the conversation, another CEO from our group made a comment along the lines of, “Indians need to spend more. They need that drive and motivation to buy things for us to really grow like China.”

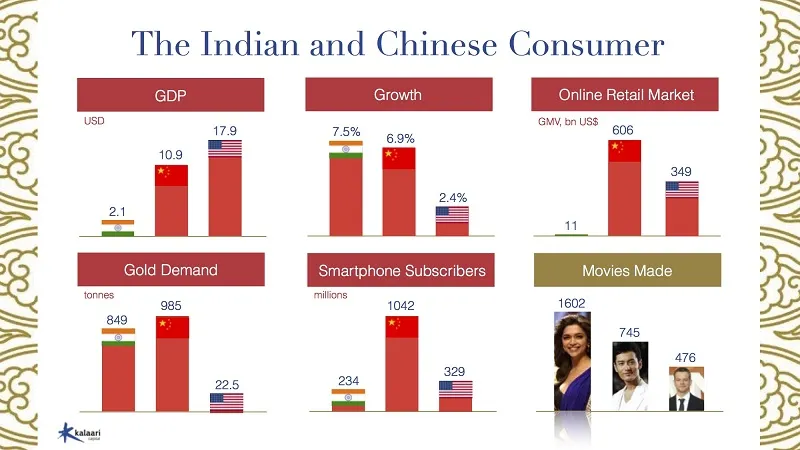

While such vehement support for materialism and excess may sound unusual, the contrast between Chinese and Indian consumerism still rings true. To return to the travel example, in 2015, Chinese tourists spent $215 billion abroad, making them the highest spending tourists in the world. In contrast, Indians spent only about $12.3 billion.

Chinese consumers spend a lot, they can and will pay for products they want, and this provides rich ground for startups to serve their needs better. In a 2013 survey on materialism, China topped the chart with 71 percent of Chinese respondents saying they measure their success by the things they own. India followed in second at 58 percent. Contrary to the conclusion of the dinner conversation, Indians are not too far behind the Chinese in terms of the motivation to buy and be represented by possessions.

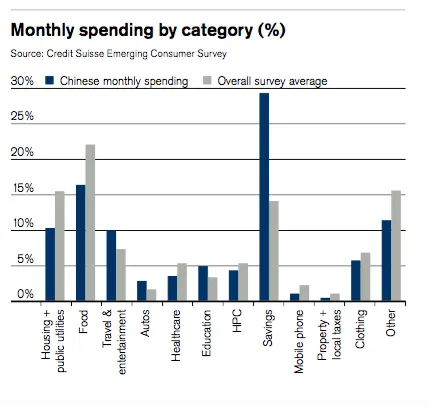

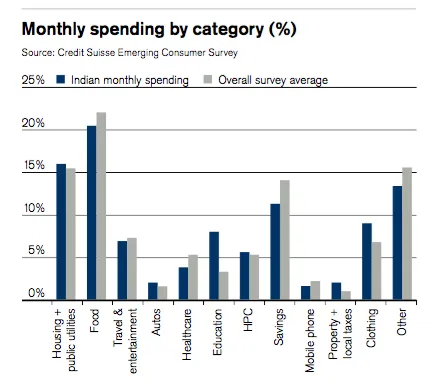

Yet, the claim that Chinese consumers spend more is incorrect. On average, Chinese consumers save almost 30 percent of their monthly income, while Indian consumers save just under 12 percent. Though Chinese consumers spend three percent more of their income on travel and entertainment, Indians spend more on health and personal care, clothing, and other non-necessity expenses (Figure 1 and 2).

The difference is not how materialistic Indians are, nor their willingness to spend versus save, as the dinner conversation suggested, but perhaps in who is spending, and how much. India has one of the widest wealth gaps in the world, wider than China. In India, the richest one percent own 53 percent of the country’s wealth. In China, the richest one percent own around 33 percent of the wealth.

A few Chinese investors we met attributed the differences in materialism, consumption, and wealth distribution between China and India to a choice made many decades ago, when China picked manufacturing and India picked services. Services develop a smaller, highly-skilled workforce. In contrast, manufacturing offers opportunities at all levels of society. One investor claimed that the profitability of e-commerce in China didn’t come with increased internet penetration, or broadband quality, but rather the rise in incomes through manufacturing across all classes. He thus projected a similar e-commerce bottleneck for India until it pushes manufacturing, or adopts some mechanism for lifting incomes at all levels.

Chinese writer Yu Hua claims there is an earlier historical root to China’s consumerism, before manufacturing brought money. In China in Ten Words, he claims, “Behind China’s economic miracle there is a pair of powerful hands pushing things along, and their owner’s name is Revolution.” When the Communist Party came to power in 1949, it rose with a promise to carry out a revolution - to dismantle China’s imperial past and to bring wealth to the people. The Revolution rose with violence, conquered with violence, and ruled with violence, culminating in the Great Leap Forward and the Tiananmen Square Protest of 1976. “Revolution never disappeared but simply donned a different costume.” Yu claims the obsession with subservience to authority that characterised Mao’s Communist revolution was translated into an obsession with money during Deng Xiaoping’s economic revolution. And so it is, he says, “A China ruled by politics has transformed itself into a China where money is king.”

India may not be driven by such revolution, but nevertheless, the data show that Indians are rapidly building a habit of consumption. A Credit Suisse survey found that between 2013 and 2014, India saw a 22 percent growth in the number of respondents that had purchased a holiday, compared to China’s five percent. In India there was a 15 percent growth in the number of respondents that had purchased a smartphone, compared to China’s eight percent. Indians, like their Chinese counterparts, are spending, and increasingly can and will pay for what they want.

- The borders of the internet

Upon landing in China from Bengaluru, I pulled out my phone to check my email. It took five minutes of unsuccessful attempts to reload my inbox for me to realise I was now in the realm of the Great Firewall, within which Google, Facebook, Twitter, The New York Times, etc., are blocked. Across India’s border into China, the internet is a different creature. At one level, China’s internet is constrained by the government. Yet at another level, speedy and cheap data/Wi-Fi have enabled it to touch the deepest corners of the country, and to be used far more frequently than we could imagine in India. The Great Firewall and high internet penetration enable businesses to succeed in China that, at least today, would not in India.

One investor in Shanghai told us that The Great Firewall was key in enabling the early Chinese tech companies (Baidu, Tencent, etc.) to grow and flourish, by incubating them from global competition. These companies, in turn, played a crucial role in the growth of China’s tech industry. Another investor in Beijing said that India has not seen any large, purely online businesses like China has (Baidu, Youku, Weibo, etc.), perhaps because Indian startups must compete with big, well-resourced, purely online businesses like Google, Facebook, and Twitter.

Indian companies are not only constrained by global competition, but also by the limited data usage in the country. A 2015 Pew study reported that only 22 percent of Indian adults use the internet at least occasionally, compared to 65 percent of Chinese adults. Only 17 percent of Indian adults report owning a smartphone, compared to 58 percent of Chinese adults. Many Chinese investors were concerned that even after India rolls out 4G and internet speeds improve, high data prices and minimal Wi-Fi penetration would cripple monetisation strategies requiring consistent internet usage.

The three listed companies we met - Alibaba, Xiaomi, and Qihoo 360 - suggested that India’s data problem would prevent business models that had worked in China from expanding to India. Such models include monetisation strategies based on advertisements, regular user data collection, and content. The data problem would not only be a barrier to expansion for Chinese companies, but as some Chinese investors noted, it also severely limits the types of Indian startups that can arise. Analysing the underlying differences in the experience of the internet in China and India enables us to recognise the perquisites for various types of internet businesses to succeed, and consider how India can meet these prerequisites to stimulate dormant startup opportunities.

- Local problems, homegrown solution

Chinese startups have long moved away from consistently adapting business models that have worked elsewhere, to solving unique local problems. As India’s startup ecosystem matures, and as entrepreneurs from more diverse backgrounds have access to the necessary resources, we may find a similar shift towards distinctly Indian problems in more localised niches.

An example of a local problem that Chinese startups are tackling is “Uber for long-distance trucking,” as one investor described it. In China, trucks are generally owned by the driver, who is responsible for sourcing clients. Once a driver has reached his destination, he usually struggles to find jobs that will take him back home, so he might drive empty. This app allows shipment companies looking for trucks to make requests, and for truck drivers to accept new jobs as soon as a job is completed.

Another example from the healthcare space is a platform that helps doctors at public hospitals manage a private practice. In China, the best doctors work at public hospitals, where they are rushed to care for many patients. In order to develop a more lucrative private practice, these doctors often want to offer better care to a few select patients outside the hospital. Recent Chinese legislation has allowed doctors at public hospitals to take on a private practice on the side. Now, Chinese startups are trying to develop platforms that enable doctors to find and keep in touch with patients they wish to include in their private practice.

The focus on local problems reflects a broader shift in the Chinese startup ecosystem towards more homegrown entrepreneurship. Like India, China’s startup ecosystem has historically had strong ties to the US. Many of the early Chinese startups and VC funds began with Chinese abroad returning to start something new. Global funds made the first foray into China, but today the VC scene is dominated by local funds. Chinese employees in the startups that succeeded have continued the startup cycle by starting their own companies. Thus, the ecosystem began with VCs and entrepreneurs who had global education and work experience, but is now almost entirely homegrown, with fewer Chinese returnees.

More diverse entrepreneurs are entering the Chinese startup scene as resources and information proliferate through the internet. Entrepreneurs from traditional businesses are creating a new generation of startups, called Internet Plus in China, bringing offline industries online. The lesson for India is the necessity of fostering more inclusive and homegrown entrepreneurship, as China has. Including people from diverse backgrounds, with diverse understanding of local problems, can produce solutions catering to niche markets, and disrupt traditional industries that would otherwise not come online.

- The New Asian Tigers: Copycats of the East?

I’ve often overheard casual, politically incorrect comments in India and abroad along the lines of “Indians have a rote memorisation education system, so they can’t be creative,” or “China can’t innovate, they can only steal.” Justifications of such statements sometimes suggest Alibaba, Snapdeal, and Flipkart are Amazon knockoffs, or Ola and Didi are just copies of Uber, or Xiaomi is relentlessly mimicking Apple. It is obvious that none of these claims is entirely true, but my recent trip to China illustrated to me just how untrue they are.

Firstly, the idea that Indian and Chinese startups are knockoffs that solve problems that American companies already have ignores the immense creativity required for localisation. If this weren’t the case, Amazon and Uber should have handily dominated China ‑ which they did not. If these companies are rapidly ramping up in India, it is partly because they’ve already learnt the pain of losing one billion people once.

Moreover, when one looks closely at the details of Chinese business models, there are marked differences from their supposed American equivalents. In particular, many Chinese companies have built massive ecosystems to enable rapid expansion into new sectors, and better monetisation. When we visited Alibaba, they told us Jack Ma’s long-term vision for the company: “Alibaba is a data company.” Alibaba leverages cross-business data to monetise in new sectors. For instance, AliSports sponsors sporting events, operates stadiums, etc., and then targets users with tickets and merchandise based on purchase data from Taobao, and financial data form Alipay. Similarly, on AliTravel, you can check out of a hotel and pay later if your credit score on Alipay is high enough.

Xiaomi, too, has an extensive ecosystem. When we visited the Xiaomi office in Beijing, we were told, “Xiaomi isn’t a core technology company. We’re an online brand.” Xiaomi’s strategy is clear: sell good hardware with low margins, provide a great UI through relentless user testing, and monetise through ads and games. Xiaomi is one of the largest game distributors in China. It has its own ad network and 20 apps, which it uses to push ads directly to a user based on phone usage. Xiaomi invests heavily into two areas: (1) music, media, unique content, etc., to improve the user experience; (2) hardware to increase the number of SKUs on mi.com (currently has ~1000 SKUs) to drive traffic to the site. Xiaomi makes roughly 70 percent of its sales through mi.com, and it tries to do so in order to engage the customer with their unique brand, and push their Internet of Things (IOT) products. These products include air purifiers, water purifiers, rice cookers, fitness bands, etc., which can be controlled through the phone. Their vast ecosystem in games, ads, content, and hardware thus enable the simple goal of being an online brand.

Apart from producing businesses of mammoth proportions in both breadth and depth, China is increasingly trending towards technical innovation. Almost every single investor we met said they are investing in AI, smart devices, and other hard tech companies. While it might be a while before India will be home to a culture of serious technical innovation, or even ecosystem companies, it will likely continue to develop unique businesses and products that break away from the mold of Western companies more and more, as China slowly has.

Conclusion: The story of tea

Consumed by the problems of the present and forecasts of the future, we often forget to observe that we forever stand on the border of history, from which the present can be observed in humor and irony. It was only about 200 years ago that claims of chronic intellectual property theft were directed Westward. By the 19th century, tea was a national addiction in England, and the British East India Company was struggling to fund its tea trade by selling opium produced in India to China. Tea production was a great technology in its time, and it was a Chinese secret by imperial orders from the Forbidden City. The EIC knew if it could discover how to grow tea in India and sell it to the British consumer directly, its profits would improve. In 1848, a Scottish botanist named Robert Fortune was sent dressed as a Chinese merchant into the heart of China, which was legally closed off to foreigners. He collected tea plants, transported them to India alongside some Chinese tea growers, and eventually set up the first plantations in Darjeeling.

What does the story of tea reveal to us about the present?

- The New Asian Tigers: Copycats of the East? Being a copycat is a critical ingredient in the process of cutting costs, adapting the copied to increase revenue, and reinvesting profits in innovation. Today, China is moving into the final stage of this process, while India follows close behind.

- Local problems, homegrown Solution. Masala Chai only became popular in India in the early 20th century, when the British-owned Indian Tea Association promoted tea breaks in factories in order to increase domestic tea consumption. Much to the Association’s chagrin, the Indian workers took the British-style tea (with milk and sugar) and added spices, even more milk and sugar, and reduced the tea content so that they had to buy less tea. The local problem was cost, the entrepreneurial chaiwallahs created a homegrown solution. Now, variants of their chai are enjoyed in a Starbucks in Beijing or a London cafe as much as on the streets of India. Enabling diverse entrepreneurs enables diverse solutions to niche problems, and sometimes, this can have global impact.

- The borders of the internet. Keeping out competition has its value, but keeping it out for good is difficult to sustain, particularly when your goods are being sold to a global market.

- Manufacturing, money, and materialism. The British tea obsession was spurred in part by manufacturing during the Industrial Revolution. While tea was already popular amongst the aristocracy, it reached the masses as a stimulant used by factories to increase the number of hours labourers could work. It was also manufacturing that drove consumption across all levels of society for aspirational goods, such as fine tea. This consumption is what ultimately drove the EIC to pursue manufacturing its own tea in India. Manufacturing and materialism, from the beginnings of industrial history, have been inextricably intertwined.

- India is just x years behind China. Chai is derived from the Chinese word for tea, cha. It is unclear whether India will follow China’s path, but it is without doubt that the two countries have influenced one another deeply through words, caffeination, and an intersecting history. As the internet brings these countries together through startups, perhaps the many centuries of looking to the West will slowly be reversed. Perhaps instead we will be peaking over the Himalayas for inspiration, collaboration, and mutual growth.