10 shocking realities of caste in India

Caste is both a historical truth of the Indian subcontinent, and a reality of modern-day India. Some of us are still unaware of the extent to which caste remains an ordering principle in our society today. Caste is present in a massive way in most of India and caste-based discrimination and violence takes place across the nation. In metropolitan cities too, caste has its ugly presence, even if not in obvious ways.

If we want to beat caste, we need to understand it. But first: we’ll have to concede that it is a problem.

Laws of Manu

Integral to understanding caste is this Hindu scripture, which has shaped the way the religion has been practised in India. While the Vedas are more philosophical, the Laws of Manu detail how Hindu society must function and the traditions and rituals the people must abide by. It shows how deeply-rooted caste is in Hinduism that this fundamental text details the “number of paces (steps)” a person from a certain “unapproachable” caste must keep between themselves and a Brahmin, and the precise economic, social and physical punishments for any transgression of these mandates. This disturbing passage is a direct quote:

“If a shudra mentions the name and class of a twice-born contumely [i.e. without proper respect], an iron nail, ten figures long, shall be thrust into his mouth.”

There aren’t four castes, there are 5,000

A major misunderstanding is that there are only four castes: Brahmin, Kshatriya, Vaishya and Shudra. These are in fact the Varnas, which are considered ‘supercastes’. However, castes are often regional, and divided on the basis of not just profession. Profession is a minor part of the division that is mainly hereditary, based on different traditions and social status, and on degrees of untouchability. And the “untouchable” castes: the main victims of this system of oppression, are not even mentioned in the Vedas. The Dalits, or Scheduled Castes as the government recognises them, form a fifth varna kept out of the system.

Ambedkar’s radical thesis

Freedom fighter and great thinker B. R. Ambedkar, in his Annhilation of Caste, made a number of groundbreaking claims – the most controversial of which is that Hinduism itself has no meaning without caste. He called Hinduism a “collection of castes” that came to be defined as a religion and a culture only when Islamic culture came to India on the backs of foreign invaders. This idea was so radical that progressive intellectuals of the time banned the book.

Caste beyond Hindus

But to think caste is restricted to Hindus is an even bigger folly. Ambedkar, when he converted to Buddhism, along with thousands of Dalit followers near the end of his life, actually approached world’s two biggest religions first: Islam and Christianity . He was told his followers would not receive equal treatment in either of their religions: because in the Indian subcontinent, there are castes among Muslims and Christians as well. So the Dalit would have become Dalit-Christians or Dalit-Muslims. Untouchability and caste are cultural artifacts and social realities that have superceded religion.

Caste: punishment from the afterlife

But religion remains a justification and explanation for the atrocities of caste. The specific trap that caste locks one in is enforced by the Hindu idea of karma, which states that what you have done in your past life is responsible for your fate today, and your actions in this life will affect your birth in the next. If you’re born as Dalit or Shudra, it is believed it’s because of crimes in your previous life. And if you rebel or misbehave now, you’ll be born in a lower caste in your next life.

A small minority has social, economic, political power

The Mandal Commission Report in 1979 opened the eyes of the nation to how alive caste still was. By finding out the socioeconomic status of different castes, it uncovered startling evidence. Upper caste still held economic and social power, controlling the media and many political parties. An overlap was found between caste status and economic status, and certain occupations, like sweeping, were still the domain of the lower caste. Not much has changed since 1979.

‘We were made to sit separately from the other students’

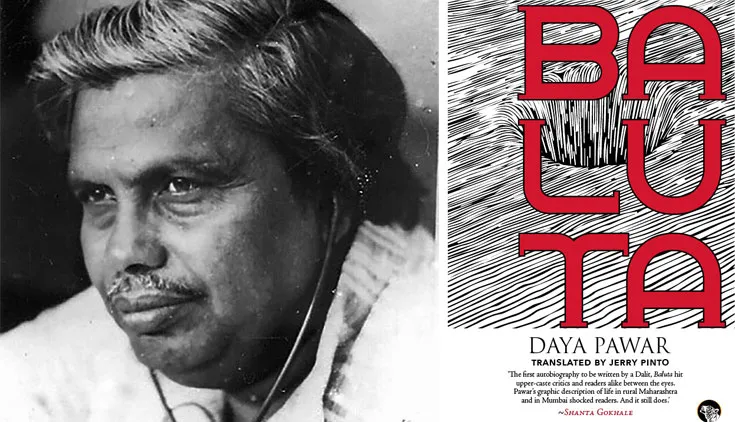

Since the seventies – but mainly in the last three decades – Dalit autobiographies have become a big way for the world to know the atrocities perpetrated by the caste system, from the perspective of the worst victims. The most disturbing things about accounts like Baluta by Daya Pawar, is that discrimination is part of their normal everyday existence. It is not a one-off instance of honour killing but has permeated into everyday lives, like being made to sit separately at school. Food cooked by Dalits is not eaten by upper caste persons. They are supposed to take water from a separate well; they live in a separate enclave, a ghetto within the village.

Every day, 4 Dalit women are raped by non-Dalits

The National Crime Bureau’s official government statistics for 2012 tell us that every 16 minutes, a non-Dalit commits a crime on a Dalit. 1574 Dalit women were raped and 671 Dalits murdered in 2012. In Arundhati Roy’s eye-opening essay The Doctor and The Saint, she cites another 2009 report on untouchability in Gujarat, where –

most villages forbade inter-caste marriage, Dalits touching utensils belonging to other villagers, Dalit priests participating in religious ceremonies taking place in non-Dalit areas, and Dalit panchayat leaders having tea in special ‘Dalit’ cups or not drink at all.

The horrific Devadasi practice

Even today, in a village in Madhya Pradesh girls born of the Devadasi (meaning those who serve God) caste are forced at the age of 12 to renounce everything and dedicate themselves to the temple. This means life-long enforced prostitution, wherein any man from an upper caste, as he chooses to, can have intercourse with her every night.

Here’s The Guardian article and Ritesh Sharma’s documentary The Holy Wives, if you can handle it.

Untouchability by any other name

More dangerous is subversive untouchability: which remains in households that have maids or servants or even drivers. The insistence on them drinking from different glasses, not sitting at the dining table with the “family”, and having separate utensils are all practices, unfortunately, unique to India.