How healthcare can become sexy

Ask any VC about the market potential for healthcare and you will almost always get an extremely optimistic response on the enormous scope for valuable businesses to be created in this space.

There is no denying that the market for healthcare firms is indeed very large and evergreen as everyone wants to live long and healthy lives. However, an odd moral dilemma is triggered when it comes to making an investment decision.

Image credit: Shutterstock

Allow me to elaborate. Time and again, entrepreneurs have pitched their healthcare businesses to me using arguments such as,“How can you deny/ignore that the problem of X million people suffering from Y disease has large business potential? Don’t you think it's a problem worth solving?”

Ironically, such moralist statements can often create a vicious deadlock, where a healthcare business’ potential for social impact is at odds with a VC’s capitalistic ambitions.

But why? Consider the following examples :

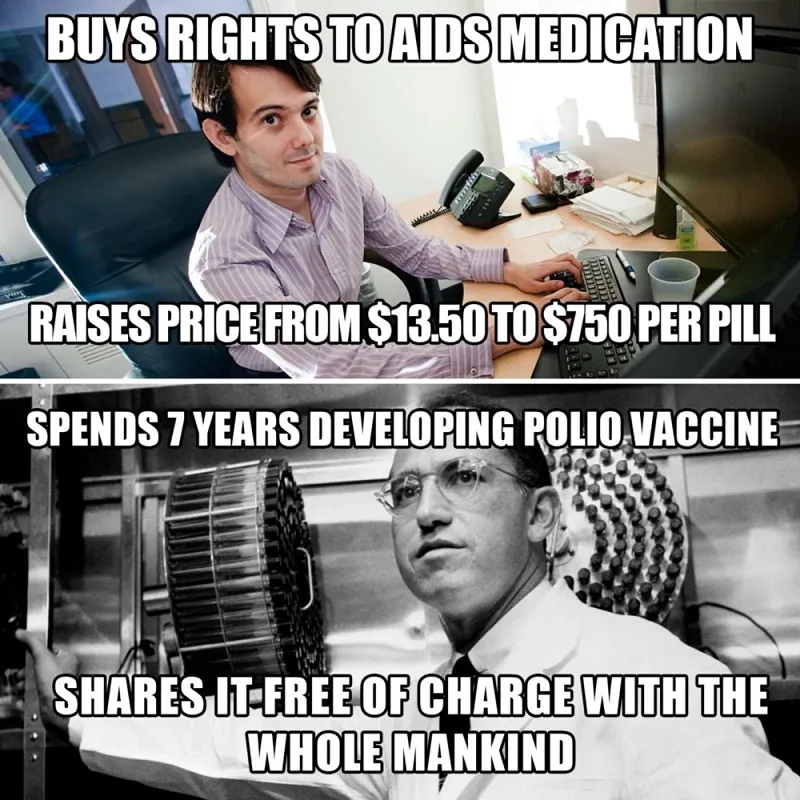

- Jonas Salk, widely credited as the inventor of the Polio vaccine, has been celebrated for not patenting the vaccine. By some estimations, Salk forfeited $7 billion by not patenting the vaccine that is now delivered to most infants on the planet. Today, he is celebrated for his magnanimity, capped by the quote “There is no patent. Could you patent the sun?” As time has passed, the possibility that the vaccine could not be patented seems to have been forgotten.

- In 2015, Turing Pharmaceuticals purchased the rights to the drug Daraprim for $55 million, a drug that can be used to treat patients with compromised immune systems, such as patients suffering from AIDS and certain kinds of cancer. Soon after acquiring these rights, Turing increased the price of the drug from $18 to $750, putting its Founder Martin Shkreli in the limelight as the world’s ‘most hated man’.

In the wake of Jonas Salk’s generosity, Shkreli had apparently done something unthinkably wicked: charge a premium price for an incredibly valuable product. Memes like the following were an obvious consequence :

As valuable as Jonas Salk’s contribution to the world has been, he might also be responsible for creating a paradigm where patients now expect medical solutions to be available for free, or at highly subsidised prices.

The fact that healthcare businesses and practitioners need to have significant incentives to provide such solutions has been conveniently ignored.

Examples of such a moral dilemma also arise in the world of doctors and their patients. During my due diligence on a few healthcare business models, I have had the opportunity to speak to quite a few doctors and understand their pain-points in elaborate detail.

In the case of doctors who had built significant credibility and got most of their business through referrals and consultations as a family doctor, the most common pain-point was, without exception, along the lines of

My patients call or WhatsApp me at odd times during the day and expect me to give them a diagnosis or remedy rightaway. I understand that they are loyal and returning patients and that they want a speedy recovery, but I think it is unfair that they expect to get a free consultation from a medical professional. I never deny their request because they might be upset and offended and think that I am not being sensitive to their condition.

How many of us have been guilty of assuming that it is the doctor’s ‘duty’ to ensure we are healthy, and have overlooked the fact that for the doctor, it is a full-time profession that earns him/her a livelihood?

Sadly, the expectation of being healthy has led us to the depraved notion that we need not pay a premium for healthcare products and services.

This is the deadlock I referred to earlier, where both VCs and startup businesses need to come to terms with the many difficulties associated with extracting value from innovation in healthcare. Is there an example, then, where an innovation in healthcare has been widely accepted and monetised?

An innovation that is so ubiquitous that it is used by more than 50 percent of the world’s population, who accept it as the best solution for their problem?

Such is the success of this invention that, contrary to what we have seen earlier, many of its users (patients?) happily pay a premium price without a second thought, not because they fear a negative outcome, but because they feel the product adds to their overall appeal.

It turns out that such an example does indeed exist.

In fact, a majority of you might be using it right now to read this post, but be completely unaware that you are benefiting from perhaps the greatest healthcare technology of modern times.

Eyewear

Image credit: Shutterstock

Wait, what?Did I just classify eyewear under healthcare?

I did. Let me explain why. If you are one of the estimated four billion people in the world who use vision correction products such as spectacles and contact lenses, think back to the time when you first decided to give the glasses a try.

Your first pair of spectacles (or contact lenses) was probably the result of a doctor consultation, followed by a prescription.

Within no time of wearing the first pair, you would have loved the new crystal-clear HD vision and the freedom from those annoying headaches.

Most wearers agree, and so did Newsweek magazine. In 1999, 'Reading Glasses' was the first entry to be featured as one of the most important inventions of the last 2,000 years with an extremely cogent rationale,

Simple pairs of spectacles have effectively doubled the active life of everyone who reads or does fine work — and prevented the world being ruled by people under 40.That alone gets them into the inventions pantheon, but glasses also foster the mind-set that people need not accept the body nature gave them, and that physical limitations can be overcome with ingenuity.

Perhaps it is no coincidence that the invention of reading glasses was soon followed by Johann Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press around 1450 and, eventually, the release of the first newspaper, the London Gazette in 1665.

With the proliferation of so much reading material, the mass consumer market wanted in on the action, and spectacles were the easiest way for someone with less-than-perfect vision to see the world (and read about it) in all its glory.

That spectacles are an outlier in the way they have become mass-adopted can also be observed from the fact that comparable augmentations such as dental braces, crutches, wheelchairs, or hearing aids, are, to this day, associated with a handicap and correspondingly, embarrassment to the wearer.

In the case of braces and hearing aids, in particular, the cool new trend is to make them invisible. Take the case of Victorian Hearing’s ad below :

While it drew a lot of attention, the company had to withdraw the ad because of customers who were offended by the messaging that patients with hearing aids should be embarrassed.

The irony of the situation aside, clearly it isn’t a trivial matter for a medical device to dodge the possibility of intense consumer hatred and gain mainstream adoption.

Spectacles, however, have become a product of universal usage and adoption because of the many positive associations that came to be formed with it.

Today, spectacles and sunglasses are widely considered fashion accessories, with many leading fashion and apparel brands offering up their own collection. The buying decision, almost always, is entirely based on the aesthetic appeal of the frame and the brand, and has very little to do with the lens that actually ‘corrects’ vision.

Is it possible that the success of glasses, as a medical solution for vision correction, and the profound impact it has had on the quality of human life, was facilitated by it being marketed as a status symbol and a fashion accessory, and not a healthcare product?

And might this also explain how Fitbit achieved breakthrough success, not as a wellness tracker, but as a cool band that made its wearer appear tech-savvy?

Perhaps success and consumer adoption in healthcare is reserved not for firms that emphasise the morbid nature of the suffering they are saving us from, but for those who can elevate their product to a source of pride for the customer.

(Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of YourStory)