After many shutdowns, online grocery in India finally takes off

The world has changed radically for online grocery startups in India in the past few years. Three to four years ago the buzz was around grocery sites shutting down. Now, the survivors and new entrants are thriving.

The top five online grocery startups in India have raised over $120 million just this year. Four years ago, a number of startups had come up in this sector but most shut down pretty soon mostly due to lack of investment and customer base.

"Out of about 40 beginners, we are among the very few who survived,” says Hari Menon, Co-founder of Bigbasket, which was founded in 2011.

Now BigBasket, along with other survivors ZopNow and Localbanya, and the new kids on the block like Grofers, PepperTap, and Jugnoo are expanding rapidly, launching in new cities, hiring new talent and raising fresh funds.

So, what changed

“The biggest change is the habit change of consumers—to buy grocery online. We are changing the way people shop for grocery,” says Mukesh Singh, Co-founder and CEO of ZopNow. The startup was founded in 2011 and had an inventory model. ZopNow changed this model earlier this year and now partners with hypermarkets to source products and is targeting over $80 million in revenue this fiscal. “The increased consumer traction has helped attract investment in this category which further accelerates the process.”

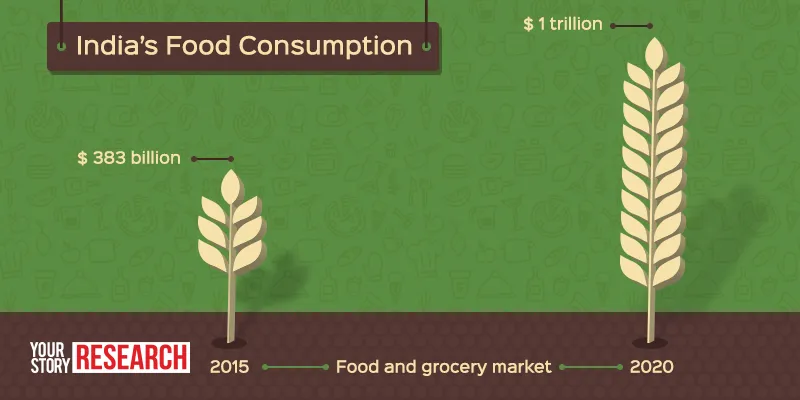

The food and grocery industry in India is now worth $383 billion and is expected to touch $1 trillion by 2020, according to a study by advisory firm Technopak. This is the market these startups are targeting.

Despite the large market size, experts like Arvind Singhal, Chairman of retail advisory firm Technopak, say the growth these startups have registered has been surprising. This is because grocery is a tough segment to crack online even globally. Poor execution had led many an e-grocer in the US--Webvan, HomeGrocer and PublixDirect—to bankruptcy in the last decade.

“This is a complex, execution-oriented business; understanding the execution and supply chain makes the real difference,” says Hari of Bigbasket, the only major player that still maintains inventory. The company, the largest in this segment, operates in seven cities and is targeting $ 1 billion revenue by end of FY 2017.

Last-mile logistics and procurement are the two areas that complicate operations in this segment and each startup is tackling these challenges differently.

Bengaluru-based BigBasket is expanding its warehouse network and going to smaller towns. ZopNow’s new model has seen them partner with hypermarkets like More and HyperCity. Bengaluru-based ZopNow and its customers have real-time visibility of this inventory. ZopNow handles the pick-up and delivery.

The new companies have opted for a hyperlocal model. Grofers, which has raised $45 million in funding just this year, started out as a provider of on-demand delivery services to local stores. Late last year, the company launched its mobile app through which consumers can place their grocery orders.

“When we started off in 2013, nobody had built the logistics and supply chain needed for grocery delivery. Of course, to get here, we needed that initial e-commerce boom,” says Saurabh Kumar, Co-founder of Gurgaon-based Grofers, which fulfils orders by partnering with local stores.

The initial stages were tough as the e-grocers needed to educate and convince merchants of the advantages of coming on an online platform. Hiring and training the workforce—70% of which is delivery boys—was challenging too.

Inventory-model vs hyperlocal-model

Chandigarh-based Jugnoo and Gurgaon-based PepperTap too follow the hyperlocal model. Jugnoo, in fact, started out as a provider of auto-rickshaws on demand and then diversified into using this network to supply groceries.

Grofers, Jugnoo, and PepperTap are of the view that grocery deliveries for online players are more a logistics problem than a problem of procurement. “Hyperlocal is the way forward. The burden of inventory management is much reduced and it is more time efficient. The inventory model brings with it a limitation to scale,” says Samar Singhla, Founder-CEO of Jugnoo.

But Technopak’s Arvind believes that what will differentiate the leader from the rest of the pack is its ability to make an extra margin to cover the costs of infrastructure and logistics. For this reason, he believes that inventory model is the future. “Even the biggies will need dark stores or strategically placed stores of their own,” he says.

Rahul Chowdhri, Partner at Helion Venture Partners, which has invested in BigBasket agrees, “Delivery alone does not give enough margins to make a profit. Merely being a logistics firm does not help you beyond a point. Integration of backend services is very important.”

Localbanya’s Karan Mehrotra believes that hyperlocal is one part of the ecosystem. “You must build the product that best fits the market. Most recently, we started offering grocery shopping plans via subscriptions which have been well received by our customers,” says Karan.

Biggies enter the fray

Competition has increased for the online grocery-focused startups with biggies like Ola, Flipkart, and Amazon entering the space. However, the category-focused players seem unfazed. Jugnoo, in fact, looks at players in a similar space as potential partners. “We would love to do deliveries for Amazon at some point,” says Samar.

Also, there is a belief that just throwing money at the problem won’t work.

“We have tested and optimised our service in the last three years. Simply entering a market with brand and resources is not a factor for long-term success,” says Karan of Localbanya.

Logistics in grocery is a different beast. “Their (e-commerce biggies’) logistics and supply chain won’t help here. Their orders come to the warehouse, they plan and go. But groceries should be delivered immediately,” says Saurabh of Grofers.

Full steam ahead

All companies are rapidly expanding and the intent is to capture space in the wallets of as many consumers in the top geographies.

BigBasket is now in the process of creating three lines of business—the current full-service model; a one-hour service by two-wheeler, using the expertise of ‘Delyver’ which they acquired recently; and a marketplace for speciality stores by October in tier-1 cities. The company is also set to launch in smaller cities and already operates in Mysuru.

While not adopting different models for different cities, the companies have found the need for modifications in operational processes. For example, PepperTap’s catalogue has specific products according to the region: the catalogue in South India will have ready-to-cook idly-dosa batter. Tie-ups with local stores help this localisation, says Navneet Singh, CEO of PepperTap.

Even the hyperlocal companies who want to focus only on the logistics side have realised they will need some kind of warehousing. Grofers is now urging merchants to set up warehouses for them to speed up their procurement and delivery. “We now deliver within 90 minutes of placing the order. With more merchants, our travel time will decrease again,” says Saurabh.

Founders and experts alike believe the space is still evolving and we will see newer formats and models. Says Helion’s Rahul: “If today you walk-in and buy, tomorrow an organised retailer will let you order online and pick up offline tomorrow.”