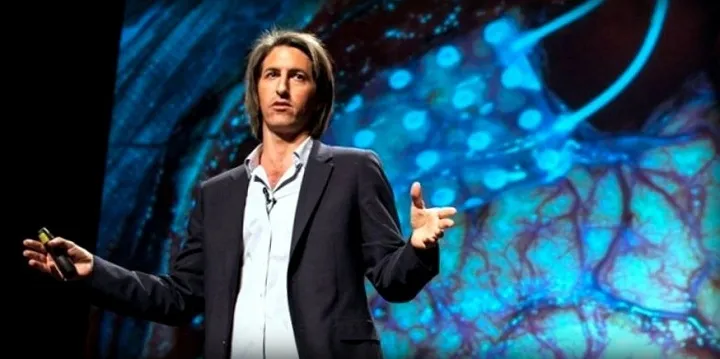

[Techie Tuesdays] How a hacker became a neuroscientist. Meet Moran Cerf

Moran Cerf can be modestly described as the hacker- turned-neuroscientist. Intrigued? Well, that tag is an understatement really. For this 37-year-old, who has worn and discarded many garbs – furniture designer, filmmaker, storyteller, hacker, academician, security specialist for Israel – is now doing some of the most cutting-edge work in brain research around the world.

How the hacking begin

Born to a French-Jew father and Israeli mother in Paris, Moran had an exciting, nevertheless hard beginning in his childhood when his family moved to Israel. They had to literally start afresh. Moran’s strongest childhood memory, one that shaped his thinking, is his introduction to the world of hacking, and the learning which followed. “Like many kids in the 80s I was fascinated by this new machine that started becoming accessible to people at time - the computer. I begged my parents to get me one even though at the time I clearly remember they were quite expensive and wouldn't do a lot for you if you weren't a programmer. Also, for me as an Israeli kid, there was the barrier of language.”

By the time Moran was 10 years old, he was fluent in English, and was hooked to playing Quests, a popular computer game those days which required written commands. He attributes much of his language skills to this game. With BASIC (computer language), he figured out the use of computer to extend his ideas rather than to just use other people's works. Moran found out the answers to ‘how to increase your life' in Mario game, ‘how to copy programs that were protected, ‘how to write your own patched to existing programs’ and so on. This in turn got him into the smaller community of programmers. So when the internet first arrived, they could share ideas which others were not exposed to. It became clear that computers opened up endless opportunities.

Computer, an impenetrable black box? Not any more

As per the rules in Israel, when Moran turned 18, he was recruited to the Intelligence unit of Israeli army where his skills as a hacker were put to use in a much larger scale. After three years of army service, it became a natural thing for him to work as a hacker. It was then that Moran started playing with hardware, actually break, burn and crash computers at their core, knowing that he can get the parts and restores it afterwards. Also, with Internet, he joined hacker communities. Suddenly this entire world of hacking translated to something tangible outside the computer. Moran recalls: “When I heard of Julian Assange recently, it struck me: "hey... I remember that name from a decade ago!" It was the same case with Mark Zuckerberg and others who were once active in the hackers’ chat rooms.”

Moran’s stages of transition with the computer is fascinating. “At first, computers seemed like an impenetrable black box. Something too hard to understand and impossible to master, with all the things one would have to learn in order to be able to work with them. But when I started, it was clearly within reach. In science and in life, I am often confronted with topics I know nothing about. And the initial feeling is to give up. But my time with the computers has taught me otherwise. Typically from knowing nothing to knowing enough to talk intelligently about things, one needs a lot less time than it first seems. And overcoming this initial fear of the black box is the first step. That is what hacking is all about,” he says.He used the same approach to study Physics when he got into the university and later on with neuroscience.

Path to neuroscience

For Moran Cerf, switching from one field to another every couple of years is generally not a bad idea. He likes to expand his horizon every decade or so. Transitions were never planned but in hindsight, it seems like they were part of a perfectly-crafted trajectory.

His shift to neuroscience started with a general interest in 'consciousness' when he was still a hacker in Israel. He used to read a lot about consciousness and forced his thoughts on it upon his friends. Moran recalls: “My job as a hacker also offered me the opportunity to travel to a lot of places, to work on-site with banks and institutes who needed security help. So I would spend my daytime working with those companies, trying to break-into their systems and evenings, I took on a project of meeting and interviewing scientists (on camera) who are interested in things I cared about. I wanted to make a documentary about the ‘science of consciousness’ with these recordings.”

Among all scientists, Moran was influenced most by Francis Crick. Francis too was a sort of hacker in 1940s and 1950s. He suggested a notion that hackers should go into science and apply their methods (the statistics and patterns identification aspects of the research). This interaction got Moran interested in neuroscience. The book "Surely You're Joking, Mr. Feynman!" describing the life of a scientist (Feynman) and the life of a city (Los Angeles) also impacted Moran. As a result, he decided to go to Caltech to have at least half as good adventures as Feynman had while studying neuroscience.

Most important lesson from PhD

The most important thing Moran learned during his PhD was that the world isn't black and white. He describes: “Coming into science, I was very much a classicist. Though Quantum Mechanics denied it, deep inside I felt I could understand things and solve problems by fully determining the underlying machine that governs the behavior. And I went ahead to do my PhD with this belief to study consciousness and derive the laws that make it tick.”

Moran worked along with Professor Ralph Adolphs on a group of people with autism. The idea was to study whether there could be a way to diagnose autism by the patterns of behavior they exhibit when looking at other people's faces. Ideally, this would have been an efficient and fast way to classify someone as autistic at a younger age and in a much cheaper way. But it never worked because the scores of the tests falling in the two pre-classified spectrums could not reflect the actual condition of the subject. When Moran took this issue to Prof Ralph, he was told something which changed his life.

“He (Ralph) explained that most of the science is somewhere on a spectrum and most people are actually not falling into the right 0/1 clustering that I tried to create (the black and white worldview). On the contrary, biology is very gray and it is very hard to force a classicist viewpoint on science and the world where most things are statistical and not deterministic.”

It took Moran quite a while to overcome his desire to fit things in boxes and to be label any phenomenon with a name and a description. This learning, he says, was the most profound education during his PhD.

Research on brain activity

Describing his research on brain activity, Moran said that at any given moment, many thoughts run through our brain, but we typically speak in one voice. We think as one person but are the sum of multiple people competing inside our head, and only the winning one becomes the “conscious you”. He tried to create experiments that educated us on the way the competition is actually running inside our brain, and the mechanisms that underlie this vying for dominance until one thought takes over and manifests itself in the brain.

Dreams and motivation

Moran believes that having the wrong dreams stops a person from pursuing his dreams. He says: “Success is getting where we want, and happiness is wanting what we got. There's a saying: If the gods want to punish us - they answer our dreams.”

He thinks that not many scientists are able to communicate their work to the general public, which results in the loss of their accomplishments. So, he keeps himself motivated by communicating his work to the masses.

Moran is a story-teller at heart. He sees all his roles as mere extension. “The hacker is a cool topic that makes people want to listen to me, because it's still rare. The neuroscientist tag - gives legitimacy to what I do and adds a level of rigor to my content, and the writing is what enables me to find ways to better-communicate my story to the world.”

Current research implications

Moran’s current research, he says, will not have any immediate implications in neuroscience as they are still midway in studying brain and understanding how it works. A possible outcome could be a BMI (Brain Machine Interface) which studies how brain encodes information to machines to control our environment in a better way. It is revolutionary for those who have lost limbs or are unhealthy, but has an intact brain. Being faster in interpreting the communication, it will open doors in controlling machines using the brain.

Message to young innovators

A common misconception is that science is for geeky guys in white robes and thick glasses. Moran says that in reality, if you want to have “an extremely cool life full of adventures and curiosities, you should pursue science.” For scientists, he recommends, nursing at least one thought-provoking question they will chase. One that will have them wake up every morning asking: “have I done something to get closer to the answer of this question while advancing science at the same time?”

He wants to tell young innovators across the world: “Don't be afraid to break the boundaries, be a hacker, a rebel, a misfit and know that it's ok. Failing in science is graceful. We'll all have failures in life at one point or another. It might as well be a failure in trying to do something that will change the world for the better. And finally, if you can frame your actions, your research and your thoughts in the way of a story, you'll find out that people want to listen, and they care much more. We are engaged in stories.”

You can follow his research work and find more about him at The C-Lab ( where C refers to Curiosity, Creativity, Cognition, Complexity, Consciousness, Consumer Behavior, Computation).

![[Techie Tuesdays] How a hacker became a neuroscientist. Meet Moran Cerf](https://images.yourstory.com/cs/wordpress/2013/11/Moran-a-story-teller.jpg?mode=crop&crop=faces&ar=2%3A1&format=auto&w=1920&q=75)