Resolving India’s Entrepreneurial Paradox: Key To Starting Up The Economy?

The article has been reblogged from Mahindra Rise. If you have a great idea and need a platform to showcase, please submit your idea for Spark The Rise- and get your project funded.

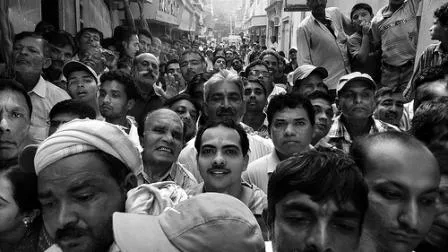

Despite its sizeable youth population, some fear that India’s much touted demographic dividend is on the verge of going horribly wrong – that the economy may not produce enough jobs to absorb the fast-growing labour force, leaving millions of young people feeling bitter and betrayed. To make matters worse, a recent Gallup study found that Indians are simultaneously the LEAST and MOST entrepreneurial people in Asia – with many Indian youths possessing strong entrepreneurial traits, though few actually wanted to start their own businesses.

“For a country as poor as India, growth should be what Americans call a ‘no-brainer’,” according to economist Raghuram Rajan in an op-ed piece published on EconomyWatch.

“Unlike many equally poor countries, India already has a very strong entrepreneurial class, a reasonably large and well-educated middle class, and a number of world-class corporations that can be enlisted in the effort to provide these public goods,” Rajan noted.

Therefore for India’s economy to succeed, “It is largely a matter of providing public goods: basic infrastructure like roads, bridges, ports, and power, as well as access to education and basic health care,” he added.

But of course, as Rajan, and most other economists, will attest, a nation’s economic growth can hardly be a ‘sure thing’. In fact, India’s annual GDP growth has fallen by 5 percentage points since 2010.

No Brainer? Not Really.

The current economic malaise is a scenario that challenges the core belief among Indian bulls that India’s private sector and, more importantly, the sheer size of its youth population, can somehow overcome weak government policies, rampant corruption and global crises to maintain economic growth in the nation.

After all, unlike China, which faces a rapidly aging population, more than half of India’s 1.2 billion citizens today are below the age of 25; while nearly 70 percent of Indians are under 40.

“History shows us that generations with an exceptionally high youth ratio create political movements that shake up their systems and leave a profound impact on history,” said Mustafi; but, “some commentators now fear that India’s much touted demographic dividend is on the verge of going horribly wrong – that the economy may not produce enough jobs to absorb the fast-growing labour force, leaving millions of young people feeling bitter and betrayed.”

This ‘youth crisis’ is further highlighted by the results of a Gallup study according to which- while more than 60 percent of India’s population possess personality traits “critical for success as an entrepreneur”, few actually start, or want to start, their own businesses.

The study also found that just 16 percent of Indian adults owned any form of business, be it formal or otherwise, today. Worst yet, just 9 percent of adults who weren’t business owners were actually thinking about starting their own businesses – making India simultaneously the LEAST and MOST entrepreneurial nation in Asia depending on your definition.

“At a glance, you wouldn’t think India has a problem [with entrepreneurship],” wrote Gallup. “Entrepreneurs have consistently contributed to the country’s vibrant growth-oriented economy since its economic liberalization in 1991… [And] entrepreneurship has become increasingly important in sustaining India’s rapid growth.”

The analysis by Gallup demonstrated that India’s entrepreneurial ecosystem ranked in the bottom quartile for external factors such as government support, culture, social capital, and access to training.“

By contrast, intrinsic factors – such as entrepreneurial talents and attitudes – ranked much higher than external factors in enabling support for aspiring entrepreneurs.”

Rich In Ideas, Poor On Support

According to the Gallup study, nearly 46 percent of Indians believed that the government was making it hard for Indians to start a business, while just 26 percent thought otherwise. Additionally, among aspiring Indian entrepreneurs, just 29 percent of respondents felt that they had sufficient access to funding to start their business in the next 12 months – down from 37 percent in 2011. This level of financial support is far lower than the average for all Asian economies surveyed (44 percent).

“[And] What does an entrepreneur need besides money? They need strong support in terms of advice,” said Mukund Mohan, who has founded and sold three Silicon Valley start-ups and is CEO-in-residence at the Microsoft Accelerator, to Reuters. ”There are not that many entrepreneurs in India, and there are hardly any in Kerala who have the expertise to be able to build, scale and sell strong software companies.

Starting Up India

Clearly more needs to be done by the Indian government to create a conducive environment for entrepreneurs. Still, as EconomyWatch has previously mentioned, private enterprises should be able to play an equally important role to grow the Indian economy – and breed entrepreneurs – in spite of the government.

That is the vision of the Mahindra Group, one of India’s largest private conglomerates, and its “Spark The Rise” campaign – now in its second year.

As part of its new corporate branding position, “Mahindra Rise”, the Mahindra Group and its “Spark The Rise” campaign have sought to create a platform where Indians can share their entrepreneurial ideas and possibly receive funding to build their start-up.

It is a noble idea with elements of international crowd-funding sites or other micro-financing platforms around. During the first incarnation of “Spark The Rise” back in 2011 for instance, Mahindra showcased 1,346 projects on its site, gave out 48 grants worth 400,000 rupees ($7,550) and provided a further 10 million rupees ($188,670) to four specially selected projects.

Now in its second season, Mahindra appears to be at the early stages of making a platform not only for grant giving, but also a place where young entrepreneurs can reach out to each other for advice and support. Setting it apart from many similar international websites, “Spark the Rise” is both a marketplace where volunteers, funders, and resource donors can find projects (and vice versa), as well as a place to find out about upcoming entrepreneurship conferences and events.

This is a bold step into the world of entrepreneurism in the digital age, especially for a company that ranks among India’s old guard of family-run conglomerates.

Sparking The Rise

For the moment however, India’s entrepreneurship landscape remains bleak. According to a World Bank report, it is still easier today to start a business in violence-afflicted Pakistan or even poverty-stricken Nepal than it is to in India, while the Global Entrepreneurship and Development Index ranks India 74th out of 79th nations in terms of an entrepreneurship environment.

Programs, such as “Spark the Rise”, that engage with every-day Indians using crowd-sourcing can thus be a way that conglomerates can both full-fill a gap left by the government, and prevent themselves from becoming superfluous. As the latest edition of The Economist points out:

Still, only time will tell if India’s business leaders can heed the call.